In the (1910!) New York Times Magazine: Collecting, hoarding, buying

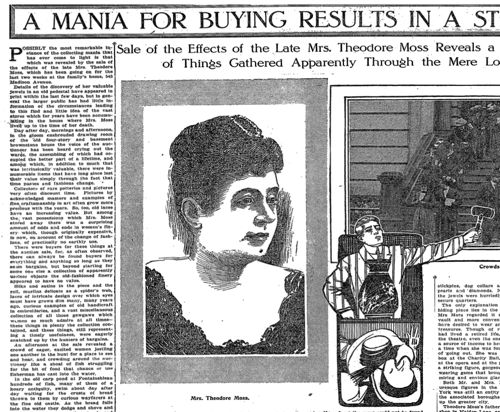

“A Mania For Buying,” announced the headline in the May 1, 1910 issue of The New York Times Magazine. The article concerns the liquidation of the “effects” of one Mrs. Theodore Moss: “A Remarkable Assortment of Things Gathered Apparently Through The Mere Love of Shopping.” While the piece hedges here and there in a not-particularly well-articulated attempt to distinguish between positive and negative aspects of material want, those words from the subhead give away the unnamed writer’s real attitude with its moralizing “mere.”

I read this article courtesy of the web site SundayMagazine.org, which makes available in PDF form “the most interesting articles” from the Times Magazine from 100 years ago, every week. I’m a great believer in reading this sort of thing: Actual contemporary views of the past, as opposed to the selectively filtered versions fed to us current pundits and gurus who twist history to fit whatever theory they happen to peddling about “today’s consumer.” (And obviously, given my day job, this particular source of special interest.) So here, what we have, is a 1910 assessment of collecting, hoarding, materialism. What does it tell us?

For two weeks, we learn, the spoils of Mrs. Moss’s “collecting mania” have been auctioned off, day after day, from her former home at 543 Madison Ave. Her name was Octavia A. Husted when she married Mr. Moss; she came from “old Revolutionary stock.” As Mr. Moss’s fortunes rose, the article allows, both he and his wife developed luxurious tastes. But back then, at least, Mrs. Moss’s “fondness for fine fabrics” and the like was no mania. Rather, it simply led her “collect” a variety of stuff — “not for hoarding, but merely because she liked looking and such things and liked to have them in her possession.” Thus she owned some real valuables; there is a long (and pretty unlikely) aside about jewels discovered by accident by someone who knocked over a pedestal that turned out to be stuffed with jewelry and gems.

But somewhere along the way – I guess after Mr. Moss died, although the piece isn’t really clear on that – something seems to have changed. By the time of her own death, Mrs. Moss had filled “at least” 10 of her four-story home’s 17 rooms with objects of all sorts. (Supposedly, in another hard-to-believe detail, she carried the keys to these rooms about … and no one else could enter.) Conceding the presence of worthwhile items, the article swiftly shifts to a judgmental, and condescending tone: “there were innumerable items that have long since lost their value simply through the fact that time passes and fashions change.” Let that be a lesson to you, readers! Time passes, fashions change, it is a simple fact that much of what the market offers will lose value.

This vaguely self-helpy tut-tutting continues:

No value, y’all.

Note, if you will, the heavy marketplace bias in these judgments. We cannot say what Mrs. Moss’s things meant to her. We can only say what they “mean” to the market, which renders its verdict in the form of a sales price, period.

Along the way, we’re given rather blatant cues to draw a line around “shopping,” particularly of the enthusiastic sort, as a foolish and distinctly feminine pursuit: Those attending the auction of the Moss pile seem to be “excited women jostling one another,” as the writer puts it, driving home his (one assumes!) point of view by drawing a comparison to fish mindlessly swarming crusts flung into their line of sight.

You may read the full article to learn how the Mos fortune was acquired, and how great chunks of it were deployed, all in rather repetitive detail. But the piece’s guiding “idea,” as we say in the 21st Century magazine game, concerns the relation between people and things. Conveniently, on this score, Mrs. Moss’s effects include a “well-thumbed” book on the subject of collecting, which our correspondent seems at least to have skimmed. Evidently this volume was pro-“collecting.” Read more

"

"

Kim Fellner's book

Kim Fellner's book  A

A