You don’t have to be a technophobe or a Luddite to dismiss out of hand the idea of reading on a machine. Maybe it is muscle memory, but there is something deeply satisfying about a “real” book, a book made of pages bound between hard or soft covers, into which you can slip a bookmark, whose pages you can fan, whose binding you can crack and fold as you move from beginning to end. E-books, by contrast, whatever platform delivers them, are ephemeral. Yes, you can carry thousands of them in your pocket, but what will you have to show for it? What will fill your bookshelves?

Then, one day, you find yourself housebound, and Wolf Hall has just won the Booker Prize, and you download a sample onto your iPhone, and just like with a book printed on paper you are pulled into the story and are grateful to be able to keep reading, and your resistance disappears, and you press the “buy” button—it’s so easy!—and that is how it starts.

— Sue Halpern in the New York Review

This post part of a sporadic and increasingly incoherent series.

Posted Under:

Consumer Behavior

This post was written by Rob Walker on June 1, 2010

Comments Off on Books, the Idea: How e-appeal happens

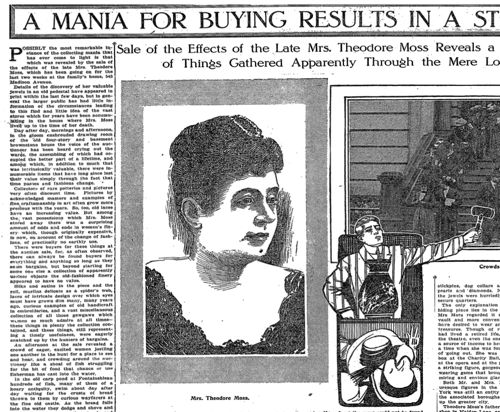

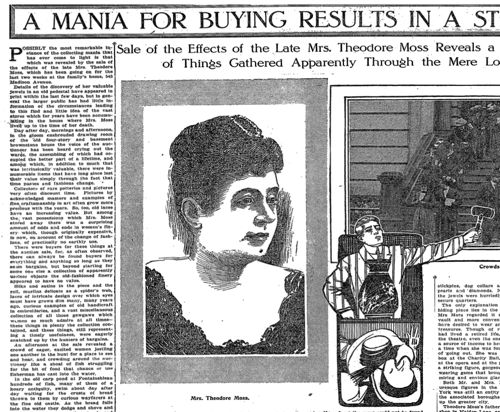

Click to get the whole 1910 article as a PDF from SundayMagazine.org

“A Mania For Buying,” announced the headline in the May 1, 1910 issue of The New York Times Magazine. The article concerns the liquidation of the “effects” of one Mrs. Theodore Moss: “A Remarkable Assortment of Things Gathered Apparently Through The Mere Love of Shopping.” While the piece hedges here and there in a not-particularly well-articulated attempt to distinguish between positive and negative aspects of material want, those words from the subhead give away the unnamed writer’s real attitude with its moralizing “mere.”

I read this article courtesy of the web site SundayMagazine.org, which makes available in PDF form “the most interesting articles” from the Times Magazine from 100 years ago, every week. I’m a great believer in reading this sort of thing: Actual contemporary views of the past, as opposed to the selectively filtered versions fed to us current pundits and gurus who twist history to fit whatever theory they happen to peddling about “today’s consumer.” (And obviously, given my day job, this particular source of special interest.) So here, what we have, is a 1910 assessment of collecting, hoarding, materialism. What does it tell us?

For two weeks, we learn, the spoils of Mrs. Moss’s “collecting mania” have been auctioned off, day after day, from her former home at 543 Madison Ave. Her name was Octavia A. Husted when she married Mr. Moss; she came from “old Revolutionary stock.” As Mr. Moss’s fortunes rose, the article allows, both he and his wife developed luxurious tastes. But back then, at least, Mrs. Moss’s “fondness for fine fabrics” and the like was no mania. Rather, it simply led her “collect” a variety of stuff — “not for hoarding, but merely because she liked looking and such things and liked to have them in her possession.” Thus she owned some real valuables; there is a long (and pretty unlikely) aside about jewels discovered by accident by someone who knocked over a pedestal that turned out to be stuffed with jewelry and gems.

But somewhere along the way – I guess after Mr. Moss died, although the piece isn’t really clear on that – something seems to have changed. By the time of her own death, Mrs. Moss had filled “at least” 10 of her four-story home’s 17 rooms with objects of all sorts. (Supposedly, in another hard-to-believe detail, she carried the keys to these rooms about … and no one else could enter.) Conceding the presence of worthwhile items, the article swiftly shifts to a judgmental, and condescending tone: “there were innumerable items that have long since lost their value simply through the fact that time passes and fashions change.” Let that be a lesson to you, readers! Time passes, fashions change, it is a simple fact that much of what the market offers will lose value.

This vaguely self-helpy tut-tutting continues:

No value, y’all.

Note, if you will, the heavy marketplace bias in these judgments. We cannot say what Mrs. Moss’s things meant to her. We can only say what they “mean” to the market, which renders its verdict in the form of a sales price, period.

Along the way, we’re given rather blatant cues to draw a line around “shopping,” particularly of the enthusiastic sort, as a foolish and distinctly feminine pursuit: Those attending the auction of the Moss pile seem to be “excited women jostling one another,” as the writer puts it, driving home his (one assumes!) point of view by drawing a comparison to fish mindlessly swarming crusts flung into their line of sight.

You may read the full article to learn how the Mos fortune was acquired, and how great chunks of it were deployed, all in rather repetitive detail. But the piece’s guiding “idea,” as we say in the 21st Century magazine game, concerns the relation between people and things. Conveniently, on this score, Mrs. Moss’s effects include a “well-thumbed” book on the subject of collecting, which our correspondent seems at least to have skimmed. Evidently this volume was pro-“collecting.” Read more

Well, funny you should ask! It’s a special issue on sustainable consumption and production, and there’s a review by me of an interesting book called Shopping Our Way to Safety, by Andrew Szasz, who makes great points about what he calls “inverted quarantine” — basically the (futile, he argues convincingly) idea that we can insulate ourselves from various ecological problems simply through individual consumption habits. I think you can read the review here.

Well, funny you should ask! It’s a special issue on sustainable consumption and production, and there’s a review by me of an interesting book called Shopping Our Way to Safety, by Andrew Szasz, who makes great points about what he calls “inverted quarantine” — basically the (futile, he argues convincingly) idea that we can insulate ourselves from various ecological problems simply through individual consumption habits. I think you can read the review here.

To my surprise, the issue also includes a nice review of Buying In.

I haven’t yet read any of the articles, but much of the issue looks promising. The introduction provides a kind of roadmap to what else is included.

Posted Under:

Consumer Behavior,

rw

This post was written by Rob Walker on May 6, 2010

Comments Off on What’s in the Jan/Feb issue of the Journal of Industrial Ecology?

Via Bookshelf Blog, click for more.

Here via the Bookshelf blog are two items of note. Above, the iBookshelf app, available for iPhone or iPad, as I understand it. Below, an iPhone bookshelf skin.

Via Bookshelf Blog. Click for more.

I assume — if you’re at all interested in this series of posts — you’ve already heard about, read, critiqued, etc the Ken Auletta iPad piece in The New Yorker. Can I possibly add anything? Not really, but in relation to this series, I did ponder this aside:

There are now an estimated three million Kindles in use, and Amazon lists more than four hundred and fifty thousand e-books. If the same book is available in paper and paperless form, Amazon says, forty per cent of its customers order the electronic version. Russ Grandinetti, the Amazon vice-president, says the Kindle has boosted book sales over all. “On average,” he says, Kindle users “buy 3.1 times as many books as they did twelve months ago.”

Obviously buying books isn’t the same thing as reading books. It’s quite plausible to me that e-books, being rather easy to buy, will set a new standard for the distribution of paid-for and unread words. Does it matter? My mixed feelings are too obvious to bother expressing.

But as it happens, I was sorting out the physical books in my office the other day, and trying to estimate the percentage of books I own but haven’t read. There are many reasons for this. Let’s just set aside the stuff that I have no intention of reading but was sent to me be a publicist, or don’t want to read but might have to at some point for professional reasons. There are plenty of the books I own that I really do intend to read — but I “haven’t found time.” How many? What percentage? And would such titles pile up more quickly on ebook “shelves”? I think for me they would.

Book-walls are just aesthetic now, just an unusually dense wallpaper: We don’t really need them for consultation. I can probably find the complete text of most of them online within an hour.

That’s from a Globe & Mail essay, A Lament For The Bookshelf. And of course when I read it I thought: Now there‘s an idea — a book-spine wallpaper pattern! [IMPORTANT UPDATE: Please see after the jump — it exists! Sort of!]

I can easily imagine a variety of choices for different consumer segments, based on what identity each one wants to project. Old-school classics? Dense philosophy? Hip contemporary fiction? Art tomes? Hilariously ironic “bad” books? Etc.

Or how about this: A flat screen that hangs on the wall and is about the size of a bookshelf, or even a book case, that displays a rotating assortment of book spines? It could be tied to what’s actually in your Kindle or whatever, or it could be a complete fantasy. There could be a subscription service so your virtual shelf is always displaying whatever got the best (https://www.maulanakarenga.org/ativan-lorazepam-online/) reviews in the Times in the past few months.

Moreover, the book spines don’t even have to be photorealistic, they could be executed in various visual styles, like this. Or, again, a subscription service so a different artist rendered the idea of the books you would like have on display, if you actually had a bookshelf.

C’mon. That could xanax happen.

[Update: Or has it happened already? More after the jump.]

Read more

“Macarons are not meant to be mainstream,” sniffs Laetitia Brock, a native of Paris.

— WSJ.

Posted Under:

Consumer Behavior

This post was written by Rob Walker on March 2, 2010

Comments Off on Socio-cultural distinction conflict via consumption practices du jour

On his blog, Dan Ariely cites recent research that he says has some implications regarding “green” consumption and the idea that one “green” purchase may give us “license” to feel we’ve done our part, we’re off the hook, and we can ignore such considerations in our next action (consumer action or other):

Through a series of experiments, Mazar and Zhong drew the following distinction between two kinds of exposure to green: When it’s a matter of pure priming (i.e., we are reminded of eco products through words or images), our norms of social responsibility get activated and we become more likely to act ethically afterwards. But if we take the next step and actually purchase the green product (thereby aligning our actions with our moral self-image), we give ourselves the go-ahead to then slack off a little and engage in subsequent dishonest behavior.

So in effect, a green purchase licenses us to say “I’ve done my good deed for the day, and now I can focus on my own self-interest.” I gave at the office, I paid my dues, I did my share — that sort of thing. How moral we choose to be at any given moment depends not only on our stable character traits but also on our recent behavioral history.

Forgive me for saying so, but there’s a similar point, based on different (but not that dissimilar) research, in Buying In. I riffed on a paper called “Licensing Effect in Consumer Choice,” by Uzma Khan and Ravi Dhar, Journal of Marketing Research, May 2006. Here, cut and pasted, are three relevant paragraphs from Buying In:

Members of one group were presented with a straightforward consumer choice: Would they prefer to buy a vacuum cleaner (a utilitarian object) or a pair of jeans (a bit of a luxury), each of which was assigned the same price, $50? About 73 percent chose the more practical product, the vacuum cleaner. Members of the other group, meanwhile, were told to imagine they had volunteered to spend three hours a week performing community service; they could choose teaching children in a homeless shelter or “improving the environment.” They were asked to explain their choice, a process meant to prod them into engaging with the idea. Then they faced the vacuum-cleaner-or-jeans choice. In this group, a majority (57 percent) opted for the jeans.

A similar set of studies indicated that subjects were more likely to splurge on fancier sunglasses or pricier concert tickets after giving to charity. The researchers concluded: “The opportunity to appear altruistic by committing to a charitable act in a prior task serves as a license to subsequently make [the subjects] relatively more likely to choose a luxury item.” In explaining their decisions after the fact, very few subjects made a direct connection between doing a good deed and their subsequent purchase decisions. Evidently, their interpreters helped them come up with other explanations. But the study strongly suggested that doing good in one area of life provided a rationale to worry less about such things in another.

There are many ways to feel you’ve done a good deed—and there are many ways for a consumer to feel ethical. That’s why the previously mentioned LOHAS population seems so huge: This caring consumer can be someone who claims to buy ecological or “green” products or simply to be a consumer of anything from alternative health care to “personal development” offerings, including yoga or “spiritual products and services.” That’s a lot of options for the consumer to buy something and conclude: Hey, I’ve done my part.

Anyway really interesting stuff, I think, and I’m always interested to see research that acknowledges all behavior happens in a context — what we do next is influenced by what we did recently and so on — instead of addressing all consumer decisions as discrete, happening in some kind of vacuum. That’s how experiments work, but it’s not how life works. For more of Ariely’s thoughts see his post.

A while back I promised I’d start writing some about books on this site, since I get so many email requests from people looking for book suggestions. I should clarify that I’m not going to review or even recommend books, per se. I’m just going to write, on occasion, about stuff I’ve read lately — whether for pleasure or for work-related obligation. Hopefully I’ll say enough, coherently enough, that you can decide for yourself whether any given book I bring up is something for you to pursue further on your own. I’ll try a couple of these and see how — or if — you react, and decide from there whether to change it up (or even whether I should keep it up).

A while back I promised I’d start writing some about books on this site, since I get so many email requests from people looking for book suggestions. I should clarify that I’m not going to review or even recommend books, per se. I’m just going to write, on occasion, about stuff I’ve read lately — whether for pleasure or for work-related obligation. Hopefully I’ll say enough, coherently enough, that you can decide for yourself whether any given book I bring up is something for you to pursue further on your own. I’ll try a couple of these and see how — or if — you react, and decide from there whether to change it up (or even whether I should keep it up).

I’ll start with Margaret Atwood’s Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth . I read it while preparing a recent-ish column. Adapted from a set of six lectures she gave in 2008, it’s very entertaining, full of interesting information, and wonderfully written.

. I read it while preparing a recent-ish column. Adapted from a set of six lectures she gave in 2008, it’s very entertaining, full of interesting information, and wonderfully written.

Obviously Atwood’s subject is debt, as an idea. Near the beginning she writes: “We seem to be entering a period in which debt has passed through its most recent harmless and fashionable period, and is reverting to being sinful.” As she demonstrates, debt as sinful, or at least shameful, notion, certainly has quite a history. But over time, that’s changed — as cultural shorthand examples she notes that while Marlowe’s Faustus was guilty of over-spending, Dickens’ Scrooge was guilty of over-saving. In Scrooge’s redemption via dropping his hoarding, miserly ways, there echoes a new ethos, Atwood argues: “Money … is of use only when it’s moving, since it derives its value entirely from whatever it can translate itself into. … [C]urrency is called ‘currency’ because it must flow.”

She concludes by turning to other sorts of costs incurred and debts owed — to the planet, for instance. She returns to re-examine Scrooge.

[B]eing a creditor of such magnitude in the financial sense, he has himself become a debtor in the moral sense, and it’s this realization that’s at the core of his transformation. Money isn’t the only thing that must flow and circulate in order to have good value: good turns and gifts must also flow and circulate …. for any social system to remain in balance.

And here she posits a contemporary creature known as Scrooge Nuoveau, who does spend money: “On himself.”

“It’s not his fault that he’s a self-centered narcissist: he grew up surrounded by advertisements that told him he was worth it, and that he owed it to himself,” Atwood writes. This figure – who “his own debtor and creditor rolled into one” — is clearly a stand-in for the Western consumer. By and large the point she makes here is the costs being piled up in the destruction of the earth — someday, we’ll pay.

For me that idea of how Scrooge 2.0 thinks about debt — what he owes to himself — is the lasting insight. I think something close to this sentiment did indeed drive a lot of consumer debt-abuse in recent years (and probably still drives a lot of spending even now). I think I’ve said this before, but to me the key question isn’t always what we want vs. what need, but rather what we feel we deserve.

If you missed it, I really recommend Michael Pollan’s cover story from the Times Mag this weekend, on food preparation as something we watch on television, rather than something we do. It’s really well done. Here’s one side note that’s particularly relevant to this site:

It’s no accident that Julia Child appeared on public television — or educational television, as it used to be called. On a commercial network, a program that actually inspired viewers to get off the couch and spend an hour cooking a meal would be a commercial disaster, for it would mean they were turning off the television to do something else. The ads on the Food Network, at least in prime time, strongly suggest its viewers do no such thing: the food-related ads hardly ever hawk kitchen appliances or ingredients (unless you count A.1. steak sauce) but rather push the usual supermarket cart of edible foodlike substances, including Manwich sloppy joe in a can, Special K protein shakes and Ore-Ida frozen French fries, along with fast-casual eateries like Olive Garden and Red Lobster.

Yes. And of course those advertisers know exactly what they are doing: Associating their processed or prepared-for-you foodstuffs and meals with the vague idea of hands-on cooking. Maybe watching someone expertly prepare a meal from scratch is something that makes you feel good, and if a can of Manwhich can associate itself with that good feeling, nonconsciously of course, perhaps that association will still lurk in your brain somewhere as you wheel through Kroger.

The whole piece is actually full of great stuff about consumer behavior, advertising, and entertainment, filtered through the lens of food. Great stuff.

It’s often said that consumers in the downturn are more often stopping to say: “Do I really need that? Or do I just want it?” And of course they are often answering that they don’t “need” whatever it is after all. This is widely read as a) evidence of new consumer virtue, and b) bad news for anything that might be characterized as superfluous, an indulgence, and so on.

This Time Magazine blog lists a few business/product/shopping/etc. categories that are apparently holding up or even thriving in the downturn. One that caught my eye: Donuts.

On the want vs. need scale, it’s pretty obvious where donuts fall. But I would suggest a third word: deserve. You don’t need a donut, but every once in a while, hey, you deserve one. You’ve cut back on so many other things, you’ve been such a frugal and virtuous person, it’s only fair (one might tell oneself) to indulge. Not because it’s something you want. Because it’s something you deserve.

Somewhat related: Earlier Consumed about “compensatory consumption.”

Sometimes people ask me why, say, McDonald’s or Coca-Cola or Nike bother to advertise at all. We’ve all heard of them, right? We’ve all decided whether or not we like them. So why waste the money? Here is my answer: Because the simple-sounding issue of salience is very important. And as backup I offer the abrupt return to popularity of Michael Jackson’s music.

Yesterday evening, Cult of Mac predicted a surge in sales of Michael Jackson music. Correct. Indeed as I type this 9 of the top 10 albums, and six of the top 10 singles, on the iTunes chart, are Jackson material.

Ah, but this was a safe prediction, because this kind of thing happens all the time — Tim Russert’s books, to name a random example, took all the top slots on Amazon.com after his surprising, and widely reported, death. Why is that? Is there something about high-profile death that makes us want to buy cultural products created by the recently deceased?

Not exactly. It’s not the death but the “high-profile” part of the equation (the attendant media/web coverage and chatter) that matters. This is for the simple reason that it makes such figures highly salient. Salience is certainly not the only element in a consumption decision, but it’s an essential one. (This is discussed briefly in an early chapter of Buying In, from which I’ve borrowed a sentence or two in the post that follows). Read more

Not exactly. It’s not the death but the “high-profile” part of the equation (the attendant media/web coverage and chatter) that matters. This is for the simple reason that it makes such figures highly salient. Salience is certainly not the only element in a consumption decision, but it’s an essential one. (This is discussed briefly in an early chapter of Buying In, from which I’ve borrowed a sentence or two in the post that follows). Read more

One other note from How Conference tweets that you didn’t have to be there to appreciate. Or maybe to loathe. This dispatch:

@danieleagee: Just heard someone ask someone else, “How do you consider yourself a creative without owning an iPhone?”

Hm.

Maybe the overheard person was kidding.

(Related: Research suggesting mere exposure to Apple logos makes people more creative was discussed in this column.)

The Times Mag‘s cover story this weekend, about Bill Clinton, opened with a scene of the former president shopping, in Peru.

The store owner showed him a selection of shoulder bags for women. Clinton selected one he thought would be great for his friend, Frank Giustra, the Canadian mining mogul, to give to Giustra’s girlfriend. Clinton said he likes picking out gifts for his friends’ wives and girlfriends.

I found that last point strange: Who buys gifts for their friends’ wives and girlfriends? I can’t imagine doing that. “Hey man, picked up this purse for your girlfriend. Trust me, she’ll like it.” I’m also trying to figure out how I’d react if a male friend of mine (or, for that matter, Bill Clinton) started buying presents for me to give my wife.

E thinks this might simply be normal behavior among people who have lots and lots of money. Or perhaps it’s just part of Clinton’s, um, general interest in women.

It struck me as very odd behavior.

Jonah Lehrer, author of the celebrated How We Decide, describes an experiment suggesting a link between what something costs and how well we think it will work.

As it happens, the same experiment is described in the decidedly less-celebrated Buying In. But that’s not why I bring it up. I bring it up because an even more powerful demonstration of the same tendency was demonstrated in a more recent study involving the fictitious painkiller Veladone-Rx.

You might remember that if you’re a regular here, because that study was the inspiration for a 48-Hour T-Shirt. The T is no longer available, but the research description remains. It’s still one of my favorite studies ever (the upshot is that people found a placebo painkiller effective if it cost a lot — but not very effective if it was cheap).

For yet another discussion of how a higher price actually enhances consumer preception of utility, see this Murketing post about paying for garbage. (That post includes, though it is not quite about, a real-world example of prices and apparel that I think is harder to rebut than the ones Lehrer offers, but that’s just my bias.)

In this item about the (to me) creepy-sounding possibility of monitoring what your friends are watching on YouTube, while they monitor you back, I was surprised by this assertion:

Many people go to YouTube without any particular video in mind — they simply go to watch something.

Really? Do you do that?

I’m pretty sure I only go to YouTube with a video in mind, or by way of a link to a specific video that’s been brought to my attention in some way or other.

"

"

Kim Fellner's book

Kim Fellner's book  A

A