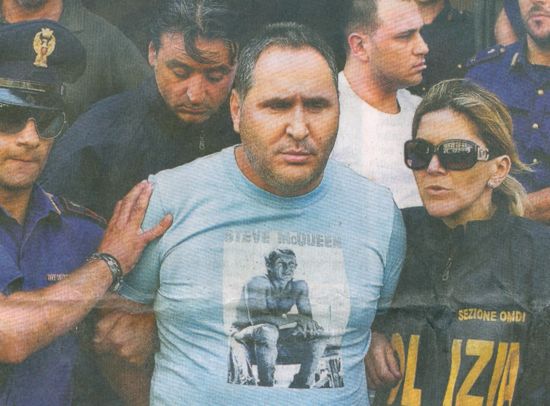

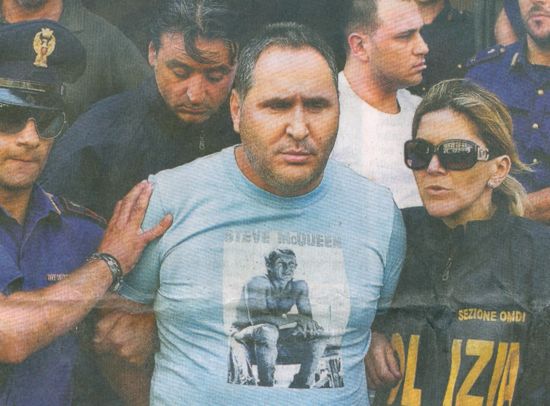

This photograph was on the front page of my Wall Street Journal this morning. I couldn’t find it online, so I cut it out and scanned it. I found other pictures of this event — the perp walk, basically, of some alleged mafia boss in Italy, supposedly responsible for 80 murders or something like that — but none were as striking as this xanax one.

First of all, please note the T-shirt that the alleged mob chief is wearing. Steve McQueen? A barechested Steve McQueen T-shirt? Where do you even get a T-shirt like that? Is it supposed to be part of disguise? It looks like a 1970s era iron-on, which might mean they’re selling them by the ton at Urban Outfitters, for all I know. But, again: Steve McQueen?

Second, however, please take note of the law enforcement officer — Polizia — on the right. Pretty fabulous, am I right? I mean, that’s not what cops look like in my city, at least. And more to the point, if you look closely at those sunglasses — they’re Dolce & Gabbanas!

C’mon. The Italian polizia hauling off the murderous mob dude in her D&G shades? How hot is that?

EXCLUSIVE FOR ALL:

EXCLUSIVE FOR ALL:

Buying pricey lux goods — along with the aura of virtuous thrift

You might decide not to buy a pair of designer shoes. Alternately, you might decide to buy a pair of designer shoes that has been marked down 50 percent. Abstaining can make you feel thrifty, frugal and (these days) admirable. Buying a bargain can make you feel all that, too. Plus you get new shoes.

Perhaps this is why there’s an interesting footnote to the much-discussed troubles of luxury brands in this time of virtuous thrift: online sellers of the discounted stuff are “flourishing,” The Economist pointed out recently…..

Read the column in the October 3, 2009, New York Times Magazine, or here.

Discuss, make fun of, or praise this column to the skies at the Consumed Facebook page.

Posted Under:

Consumed,

Lux

This post was written by Rob Walker on October 3, 2009

Comments Off on In The New York Times Magazine: Luxury e-tailers

I’m not sure how interested you are — or how interested I am — in Anna Wintour’s take on virtue, frugality, the new consumer, and all that. But I was amused by this:

I don’t think anyone is going to want to look overly flashy, overly glitzy, too Dubai, whatever you want to call it.

“Too Dubai.” I have to remember that .

THE SWEET PAYOFF

THE SWEET PAYOFF

Does an $8 chocolate bar offer something besides taste to the beleaguered consumer?

This week in Consumed, a look at “compensatory consumption,” through the lens of pricey chocolate.

Their thinking is that the little boost of, say, pricey chocolate, might not be solely about mood but about responding to threats to status or competence, Rucker told me. Ideally you would respond to such challenges directly: standing up to a boss who is pushing you around, demonstrating skill to silence skeptics and so on. But often the sources of undermined confidence are more abstract. “What’s happened in modern society under capitalism is that people have found consumer products as an outlet, a safety valve for addressing these threats in a very indirect fashion,” Rucker contends.

Read the column in the February 8, 2009 issue of The New York Times Magazine, or here. [2/9 update: Here’s me talking about the column on “Word of Mouth,” on New Hampshire Public Radio.]

Consumed archive is here, and FAQ is here. The Times’ Consumed RSS feed is here. Consumed Facebook page is here.

“Letters should be addressed to Letters to the Editor, Magazine, The New York Times, 620 Eighth Avenue, 6th Floor, New York, N.Y. 10018. The e-mail address is magazine@nytimes.com. All letters should include the writer’s name, address and daytime telephone number. We are unable to acknowledge or return unpublished letters. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.”

Posted Under:

Consumed,

Lux,

Sustenance

This post was written by Rob Walker on February 7, 2009

Comments Off on In The New York Times Magazine: Premium chocolate

The WSJ has a story about lux brands cutting prices. It would appear they have room to do so:

Luxury-goods companies don’t disclose margins for their individual brands, but Louis Vuitton, one of the world’s most profitable labels, is estimated to have a margin of 45 cents on every dollar.

That’s not additional cost due to design or materials or other quality-related expenses in the production process that are passed along to consumers. That’s the markup. That’s profit.

That’s amazing.

A piece in Salon offers a debriefing on the subject of “What’s up with black names, anyway?” Apart from being a generally well-done overview of the subject, it points to a March post on a blog called Stuff Black People Hate, titled “Stupid Names.” The category of interest to me is “Luxury Latch-Ons,” regarding which the blogger opines:

For whatever reason, black parents all over the country decided that naming their children after expensive things would bode good fortune for them throughout their lives. Consequently, there are legions of unfortunate people (mostly girls, again) with names like Chanel, Mercedes, Chandelier, and even Prada (yes, I did meet a girl named Prada, and it was the worst day of my life.)

To which Salon adds:

It is true that an unfortunate culture of naming children after brands of champagne or fancy cars has sprung up over recent years. “But that’s a class thing, not a race thing,” says Cleveland Evans [ID’d as “former president of the American Names Society”], noting that he has encountered twins named Camry and Lexus who were white. If you are poor and wish a better life for your kid, a name like Lexus declares that hope.

Posted Under:

Lux,

The People's Marketing

This post was written by Rob Walker on August 25, 2008

Comments Off on Brand names. No, I mean *brand names.*

WATER PROOF:

WATER PROOF:

A bottled water criticized by environmentalists tries to detox is image

This week in Consumed, a look at the efforts of the luxury/status water brand repositioning itself as eco-friendly. Is this in response to the much-reported backlash against bottled water? Sort of.

[A spokesman’s] most surprising assertion is that Fiji was already an environmentally conscious company — and that’s part of what has been “frustrating” about the media coverage. He points to various conservation efforts in Fiji, and to the fact that the brand’s entire business model depends on the aquifer there remaining pristine.

Others, of course, point to another unchangeable aspect of Fiji’s model: getting that water to far-flung markets where people will pay a lot of money for it. Fiji’s luxury-chic status has always been directly tied to the idea that this is a rare substance from an exotic place. Which, in turn, is the issue that enrages its critics….

Read the rest in the June 1, 2008, issue of The New York Times Magazine, or here.

Consumed archive is here, and FAQ is here. Consumed Facebook page is here.

The WSJ’s Wealth Report blog notes the Day&Night watch — “an exceptional timepiece that does not indicate the time!” It costs $300,000. “An avant-garde approach, that is different and even disturbing.” Robert Frank writes:

The WSJ’s Wealth Report blog notes the Day&Night watch — “an exceptional timepiece that does not indicate the time!” It costs $300,000. “An avant-garde approach, that is different and even disturbing.” Robert Frank writes:

The company’s chief executive, Yvan Arpa, cited statistical studies to explain how the watch better reflects the time-philosophy of today’s wealthy.

“When you ask people what is the ultimate luxury, 80 percent answer ‘time’. Then when you look at other studies, 67 percent don’t look at their watch to tell what time it is,” he told Reuters.

He added that anyone can buy a watch that tells time — only a truly discerning customer can buy one that doesn’t.

And here’s the best part: The watch sold out within 48 hours of its launch.

Counterfunctionality in watches in particular and other products in general explored in this 10/27/08 07 Consumed, and followed up in a number of Murketing posts and del.icio.us links.

[Thx: Noah!]

The ever-clever Agenda Inc. has taken the time to tot up the political donations made by those with registered affiliations with “100 luxury — or near-luxury — brands.” Among these luxe-affiliated and politically minded citizens, the clear favorite appears to be Hillary Clinton, whose donations from the posh demo put her well ahead of nearest rival Barack Obama.

Details, here, include who Tommy Hilfiger, Michael Kors, and Dian Von Fursternberg, among others, have given to. Sample finding:

The most right-wing leaning couture brand is Valentino, where an employee gave $2,300 to McCain. Gucci is a hung vote with $500 to Giuliani and $500 to Obama, while the democratic ladies of Chanel are solidly behind Obama $2,800. Louis Vuitton puts $1,250 behind Obama and $250 behind Clinton. Prada is 100% Clinton country. A lone voice at Dior has given $300 to Ron Paul.

Posted Under:

Lux,

Politics

This post was written by Rob Walker on February 4, 2008

Comments Off on Agenda Inc. reveals “luxury vote”

Premium Outlets: How a new-luxury brand manages the dances with the mass market.

Premium Outlets: How a new-luxury brand manages the dances with the mass market.

There was a time when outlet centers were associated with the grubby matter of liquidating unsold merchandise to unglamorous bargain hunters in a low-rent building in the middle of nowhere. Clearly this image has evolved, and many apparel makers even manufacture products specifically for their outlet channels. About 10 years ago, the Chelsea Property Group (a division of Simon Property Group) recognized an opportunity in this low-end category: branding high-end outlet shopping. Today, Chelsea Premium Outlets operates in dozens of locations in the U.S. and abroad, including the sprawling Woodbury Common Premium Outlets, about an hour north of New York City. Current Woodbury tenants include Jimmy Choo, Tory Burch and True Religion….

Continue reading at the NYT Magazine site.

We all know the old game of snob vs. reverse snob. When a guy at Vuitton says Coach “has nothing to do with luxury” and might as well be “selling iron ore,” well, that’s kind of snobby. The reverse snob from Coach of course decries the Vuitton guy as an elitist who needs to realize that “luxury has been democratized.”

These examples are from Fortune‘s recent recap of the eternal mass/class squabble in its latest issue. All pretty familiar, but noteworthy for Isaac Mizrahi popping up to defend himself from “critics of his work with Target.” His name for these people: “brand racists.”

Brand racists! That seem like a pretty harsh upgrade on snobbery, no? And actually, I’m pretty sure I read in one of the other recent mass/class articles somewhere else that Mizrahi’s Target success actually helped him to get Bergdorf’s (or something like that) to pick up his high-end line again. But maybe they just did it because they needed one line that had a mass-y connection to avoid looking like luxury bigots: designer tokenism, in other words.

Anyway, lux context aside, it’s actually kind of interesting to consider brand bigotry. Even those of us who claim not to pay attention to logos tend have very strong feelings about the ones we would never, ever wear. Three Adidas stripes may be fine, but put a swoosh on the same object and forget it; a polo shirt with an obscure brand’s icon is okay, but not with the Polo logo. Etc. Of course we all have our reasons for our biases, our lines of thought to assure ourselves that we’re acting on the basis of rational factors and rational factors only. Then again, bigots always think that way, too.

Really, though, I suspect brand bigotry is an underrated factor in the consumer/brand dynamic: How much are we motivated not by the brands we love, but by the brands we shun? If brand and identity are (or can be) tied together, isn’t the shun factor pretty crucial? If you have a very clear picture notion of the brands you simply won’t consider associating with, it makes shopping that much easier.

No wonder department stores are segregated by brand.

Following up on yesterday’s post about Robert Frank’s book Richistan: I mentioned my favorite example of how wealthy consumers feel compelled to move on from anything that gets too widely adapted was in the category of watches. I have been interested in the watch market for some time, without ever really coming up with a good way to write about it.

Frank cites data from an organization called The Luxury Institute; in 2006, it conducted a poll of people with a net worth of $5 million or more, to learn what the most prestigious wristwatch might be. Cartier came in 13th. Rolex made the top 10, but “barely,” Frank writes. First place went to Franck Mueller, “a newcomer from Switzerland that sells fewer than 4,500 watches a year in the United States.” The brand’s cheapest offering costs $4,800. The most expensive: $600,000-plus. “Frank Mueller,” Frank writes, “has become the timepiece of choice for the New Rich.”

The interesting thing about watches as a carrier of prestige is that watches have, in recent years, become so superfluous for most of us. If you have a cell phone, you have the time on you; you don’t need a watch. And indeed, I have read that mainstream watch sales are hurting.

Luxury watch sales, however, are not hurting at all. (Recently even Timex has been repositioning to try to cut more lux-oriented deals.) One suspects that this is precisely because high end watches have very little to do with knowing what time it is. Indeed, Frank points out that Frank Muller’s “most popular watches the Crazy Hours, a $20,000 timepiece that features mixed-up numbers on the face.” Even a company spokesperson admits that actually using it to tell time can be “tricky.” Frank cites Business Week reviewer suggesting that maybe the best strategy is to wear this watch in addition to a second one that you can actually read.

Funny. But I’d suggest a different direction: Why not make a watch that is purely aesthetics-based, and does not tell time at all? Think of the design possibilities a watch could offer if you didn’t have to worry about the whole time-telling trope, with the annoying minute, hour, and second hands, which all seems pretty played-out anyway. People who pay twenty grand for a watch not only have a cell phone and five other gizmos at hand to tell them what time it is, they also have a variety of flunkies to drive them around and make their appointments for them. Leave watches that track of hours and minutes to the proles.

Because of the day job, publishers sometimes send me books, most of which I have no interest in whatsoever; meanwhile, most of the new books I really am interested in, those never get sent to me. But in a rare exception, I got in the mail from Crown a book called Richistan: A Journey Through the American Wealth Boom and the Lives of the New Rich, which I did in fact find interesting. It’s by Robert Frank, the Wall Street Journal writer (not to be confused with Robert H. Frank, the economist who wrote Luxury Fever, among other books).

Given all the detail in the subtitle, I guess there’s not much reason to explain what the book is about. It was of interest to me because I’ve mused here about the Four or Five Americas, and maybe this is one of them. Frank divides his Richistan into three (lower-middle-upper) parts: the 7.5 million households with a net worth of between $1 million and $10 million; the 2 million households with a net worth between $10 million and $100 million; and those with a net worth higher than that, which number “in the thousands.” (There are around 100 million households in the U.S., I believe.)

The middle group is most interesting to me: $10 million is a lot of money, and 2 million is a lot of people. Enough people to form something like a common worldview, or a cultural consensus, among them.

Here’s a quick bit that I found interesting in terms of how Richistan relates to the other Americas: The spending/consumption of the broad group that Frank calls Richistanis is of course motivated in part by peer comparisons, but also by something else:

Richistanis are also spending to outrun the hordes of Richistani wannabes. The growng ranks of affluent consumers are increasingly trading up to buy goods once reserved for the rich. Luxury companies, to grow sales, are happy to sell cheaper version of their high-end products to serve this new crowd of aspiring shoppers. Marketers call it “mass luxury” and, oxymoron or not, it’s made life miserable for Richistani spenders.”

I’m used to thinking about the chasing-luxury game from the non-rich point of view: How people like say, me, will buy something like a wallet with a luxury brand name attached to it, blissfully unaware that it’s just some mundane object stamped with ersatz prestige by way of one of the licensing deals that fuel lux-company profits. Clearly it’s true that if enough people like me glom onto a lux brand, the lux crowd doesn’t want to be associated with it anymore. (An extreme version: Burberry’s chav problem.)

What I’ve given less thought to is that once Richi dumps whatever I’m buying, he has to find something else to buy, with a suitable prestige level attached to it. The example Frank offers that I like the most is the watch category. More on that tomorrow.

Posted Under:

America,

Lux

This post was written by Rob Walker on June 28, 2007

Comments Off on Burdens of wealth

Beliefnet today has some material about spirituality and spending. A list of seven tips includes advice on “How to perform random acts of kindness.” (“Create a Random Kindness Budget that you give a few dollars to each month,” etc.).

All pretty straightforward, except that that particular entry ends with:

Recommended: Give the gift of chocolate by L.A. Burdick.

Is that a sponsored link? Why that particular chocolate? Is it more spiritual than other lux chocolate brands?

Weird.

Posted Under:

Believing,

Lux

This post was written by Rob Walker on April 11, 2007

Comments Off on God and chocolate

The “Outlook” column by Mark Whitehouse in the WSJ today notes that while we think all manufacturing is leaving the U.S., that isn’t quite so. For example: “U.S. production of audio and video equipment surged about 2% in December and was up 23% for all of 2006.”

So what’s being made in the U.S.? Whitehouse says it’s stuff that’s just not practical to make elsewhere.

One area of strength: high-end goods like top-of-the-line $6,000 Sony Grand WEGA TV sets and $15,000 Sub-Zero PRO 48 refrigerators, which appeal to the affluent folks who have been driving much of the growth in U.S. consumer spending….

“If the thing being sold to the U.S. market is locally customized, delicate, or very large, chances are it’ll continue to be produced in the U.S.,” says Bruce Greenwald, professor of business and economics at Columbia University in New York.

Hey, so maybe lux tastes will save the U.S. factory worker! Well, no. Of course this represesnts a “tiny fraction” of manufacturing. But even the gradual fatttening of this thin segment isn’t likely to create more manufacturing jobs. The Sub-Zero factory in Madison is producing more, but it’s not increasing its workforce.

Across the manufacturing sector, the picture is similar: To stay competitive, companies are doing everything they can to boost productivity — that is, make more stuff with fewer people. “Manufacturing in the U.S. is headed toward plants that have no people in them,” Prof. Greenwald says.

Here’s the link for WSJ subscribers.

Posted Under:

Industry and stuff,

Lux

This post was written by Rob Walker on January 22, 2007

Comments Off on Making it

"

"

EXCLUSIVE FOR ALL:

EXCLUSIVE FOR ALL:

Kim Fellner's book

Kim Fellner's book  A

A