MY grandmother, who was born in 1905, spoke often about the immense changes she had seen, including the widespread adoption of electricity, the automobile, flush toilets, antibiotics and convenient household appliances. Since my birth in 1962, it seems to me, there have not been comparable improvements.

Of course, the personal computer and its cousin, the smartphone, have brought about some big changes. And many goods and services are now more plentiful and of better quality. But compared with what my grandmother witnessed, the basic accouterments of life have remained broadly the same.

That’s the opening of a recent Tyler Cowen column, and it surprised me. Read the rest here. Whether you agree with his points about economics, innovation and income, I think the underlying point about progress and the pace of change (and how it feels) is pretty provocative and very much worth pondering. Dedicated readers may remember this perhaps-related post on this site from 2007: “Totally Wildly Uprecedented Change, and Its Precedents.”

Click to get the whole 1910 article as a PDF from SundayMagazine.org

“A Mania For Buying,” announced the headline in the May 1, 1910 issue of The New York Times Magazine. The article concerns the liquidation of the “effects” of one Mrs. Theodore Moss: “A Remarkable Assortment of Things Gathered Apparently Through The Mere Love of Shopping.” While the piece hedges here and there in a not-particularly well-articulated attempt to distinguish between positive and negative aspects of material want, those words from the subhead give away the unnamed writer’s real attitude with its moralizing “mere.”

I read this article courtesy of the web site SundayMagazine.org, which makes available in PDF form “the most interesting articles” from the Times Magazine from 100 years ago, every week. I’m a great believer in reading this sort of thing: Actual contemporary views of the past, as opposed to the selectively filtered versions fed to us current pundits and gurus who twist history to fit whatever theory they happen to peddling about “today’s consumer.” (And obviously, given my day job, this particular source of special interest.) So here, what we have, is a 1910 assessment of collecting, hoarding, materialism. What does it tell us?

For two weeks, we learn, the spoils of Mrs. Moss’s “collecting mania” have been auctioned off, day after day, from her former home at 543 Madison Ave. Her name was Octavia A. Husted when she married Mr. Moss; she came from “old Revolutionary stock.” As Mr. Moss’s fortunes rose, the article allows, both he and his wife developed luxurious tastes. But back then, at least, Mrs. Moss’s “fondness for fine fabrics” and the like was no mania. Rather, it simply led her “collect” a variety of stuff — “not for hoarding, but merely because she liked looking and such things and liked to have them in her possession.” Thus she owned some real valuables; there is a long (and pretty unlikely) aside about jewels discovered by accident by someone who knocked over a pedestal that turned out to be stuffed with jewelry and gems.

But somewhere along the way – I guess after Mr. Moss died, although the piece isn’t really clear on that – something seems to have changed. By the time of her own death, Mrs. Moss had filled “at least” 10 of her four-story home’s 17 rooms with objects of all sorts. (Supposedly, in another hard-to-believe detail, she carried the keys to these rooms about … and no one else could enter.) Conceding the presence of worthwhile items, the article swiftly shifts to a judgmental, and condescending tone: “there were innumerable items that have long since lost their value simply through the fact that time passes and fashions change.” Let that be a lesson to you, readers! Time passes, fashions change, it is a simple fact that much of what the market offers will lose value.

This vaguely self-helpy tut-tutting continues:

No value, y’all.

Note, if you will, the heavy marketplace bias in these judgments. We cannot say what Mrs. Moss’s things meant to her. We can only say what they “mean” to the market, which renders its verdict in the form of a sales price, period.

Along the way, we’re given rather blatant cues to draw a line around “shopping,” particularly of the enthusiastic sort, as a foolish and distinctly feminine pursuit: Those attending the auction of the Moss pile seem to be “excited women jostling one another,” as the writer puts it, driving home his (one assumes!) point of view by drawing a comparison to fish mindlessly swarming crusts flung into their line of sight.

You may read the full article to learn how the Mos fortune was acquired, and how great chunks of it were deployed, all in rather repetitive detail. But the piece’s guiding “idea,” as we say in the 21st Century magazine game, concerns the relation between people and things. Conveniently, on this score, Mrs. Moss’s effects include a “well-thumbed” book on the subject of collecting, which our correspondent seems at least to have skimmed. Evidently this volume was pro-“collecting.” Read more

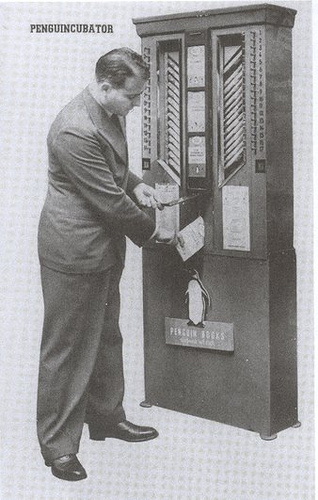

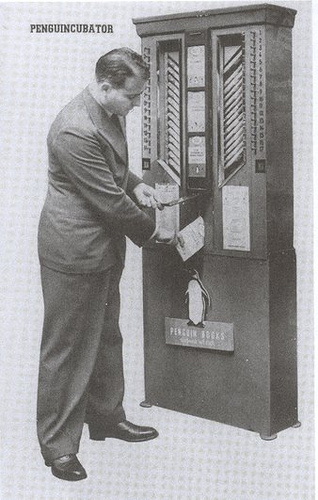

Penguincubator. Click for more.

This made the rounds recently, I believe originating with this piece on Publishing Perspectives, about Allen Lane, best known for devising the first breakout success cheap-but-quality paperback, for Penguin. Evidently Lane also dreamed up the device above: The Penguincubator, a book vending machine from the mid 1930s.

First installed outside Henderson’s (the “Bomb Shop”) at 66 Charing Cross Road, [it] signaled [Lane’s] intention to take the book beyond the library and the traditional bookstore, into railway stations, chain stores and onto the streets. It is worth noting, given publishers’ frequent timidity in this area, that this really annoyed booksellers. (Lane’s lack of trepidation is an important part of this story; worth noting, too, that he was the first English publisher of James Joyce’s Ulysses, at the Bodley Head, despite the widespread contemporary fear of prosecution for obscenity.)

In the Penguincubator we see several desires converge: affordable books, non-traditional distribution, awareness of context, and a quiet radicalism. And it’s not a huge leap of the imagination to see how these apply now. I see the same bored gaze on the bus and tube today, as people reflexively flip open their phones and start poking at email or casual games, as Allen Lane saw on the platform at Exeter in 1933. And slowly — oh, so slowly — publishers are seeing that what we are presented with is not the death of everything we trust, value and hold dear, but a similar widening vista of opportunity to that which arrived with the mass-market paperback.

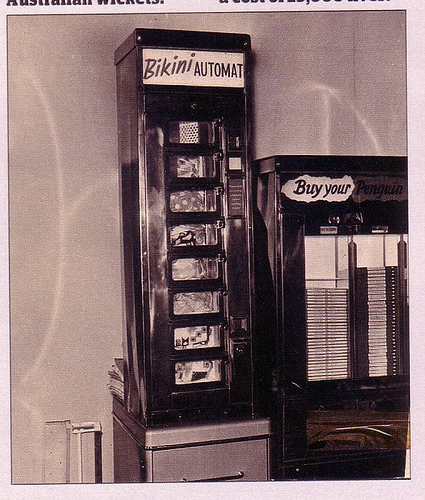

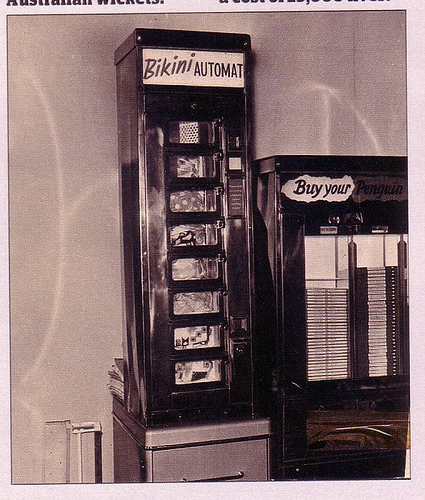

I couldn’t find out much more — like the fate of this fascinating object — but there was another picture of it on Flickr, situated next to a “Bikini Automat.”

From Flickr user Mags. Click for more.

An interesting bit in an Ad Age story notes how limited-time promotions introduced during spending slumps tend to hand around and become part of the marketplace:

Downtime promotions can be addictive

American Airlines, defending its position, in May 1981 introduced AAdvantage, the industry’s first loyalty-marketing program. United Airlines followed with Mileage Plus, a short-term promotion that was to end in 1982. Frequent-flier programs went on to become a permanent fixture in airline marketing.

Chrysler introduced auto rebates in early 1975 as a short-term promotion to clear its bloated inventory. Automakers have been addicted to rebates ever since.

And zero-percent financing after 9/11 too, right?

Speaking of oil … I just read the phrase “drill, baby, drill” for the millionth time, and it finally occurred to me to stop and think from whence this pro-oil chant is derived.

That would be, if I’m not mistaken, “burn, baby, burn,” a phrase associated with the 1960s riots. According to BlogCritics Magazine (about which I actually know nothing, it’s just the first useful thing that Google took me to), a 1965 Newsweek article about the Watts riots included “one of the first” print references to that phrase. BlogCritics continues:

Made infamous by the riots, [the phrase] was first used by a disc jockey known as Magnificent Montague when he was working in New York and Chicago in ’63 and ’64. He’s shout it any time a piece of soul music got him excited, and he brought it with him to Los Angeles where his listeners appropriated it for the arson that marked the riots. During those terrible days, his station manager and even Mayor Yorty asked Magnificent Montague to give up his slogan. He did, at least while the fires were hot, changing to: “Have Mercy, Los Angeles!”

At first I thought, well, obviously the people chanting “Drill, baby, drill” don’t know or aren’t thinking about the phrase they are referencing.

But another possibility occurs to me. It’s obviously a fantasy that America’s much-discussed “dependence on foreign oil” is something that can be significantly changed by domestic drilling, no matter what deregulation occurs. But maybe the chanters know that — and are invoking the rioters of the 1960s intentionally.

That is, maybe they simply believe in the power of destructive spectacle: If we burn it all down or in this case drill it all to nothing, then somehow, from the ashes, from the ruins, a productive revolution of some kind emerges at some unspecified time in the future. Or if it doesn’t, at least some kind of pent-up emotion, or rage, has been released and spent. And when that catharsis is complete, we can sift through wreckage and the ashes and the spent remains, and start over.

If so, I can only say quote the Magnificent Montague: “Have mercy.”

So I’m clawing my way back from a computer snafu that’s cost me a lot of time the last two days (and that may have cost me a few lost emails, just so you know).

But somehow I got sucked in this morning to spending half an hour watching Jimmy Carter’s “crisis of confidence” speech from 1979. It’s been getting some attention lately because of his comments about the energy crisis. But the whole thing is kind of fascinating — the passion of his tone is pretty startling, he seems flat-out pissed sometimes. (On the other hand, his fist-pumping is pretty ineffectual.)

Anyway, one little sound bite:

In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities, and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption. Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns. But we’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.

Cut to: The 1980s!

Anyway, the energy stuff is interesting, not so much because of his specific policy proposals, but because of the force of his argument that it’s a real crisis, “a clear and present danger,” etc. He’s practically yelling at that point.

Quite a performance. But let’s face it, Americans didn’t want to be lectured in 1979, any more than they do today.

Design For Dreaming

[ –> Details on Sponsored-Film Virtual Festival are here.]

Design For Dreaming is the final entry in this virtual festival — and probably the best-known one. It’s even been mentioned on BoingBoing.

In part I assume this is because the film is — on one level — perfectly ridiculous, featuring a sort of Audrey Hepburn type who is “Delighted!” to see new cars that are “Oh so beautiful!” or whatever. It’s campy and funny. We all love to look at this sort of thing and snicker at how naïve people used to be. And without question, Design For Dreaming is absurd. But … I think there is more to be found here than that. Read more

The Home Economics Story, Parts One and Two

“What is home economics?” this film from 1951 asks. The answer that is given: It’s partly about mastering “the equipment in a home.” It’s about physics being taught in a way “girls” would like: using kitchen appliances; indeed iIt’s about digging the fact that “Cooking is practically applied chemistry.” And so on.

Here, in other words, we have what looks like a straight-up sexist relic of a past best buried. And of course, that’s what it is — in part.

But first of all, the past is rarely best left buried. By that I don’t mean it should be returned to, but it ought to be known, and known as honestly as possible. These sponsored films may not seem like the ideal place for honesty, but usually, if you look closely, and think about what you’re seeing, things are a little more complicated than they appear. Read more

[ –> Details on Sponsored-Film Virtual Festival are here.]

This 19-minute film, “Why Braceros?,” was produced in around 1959 on behalf of the Council of California Growers. It aims to tell viewers about “the benefits of the bracero program,” The Field Guide to Sponsored Films explains, “originally initiated by the United States in 1942 to alleviate the World War II labor shortage.” This was a “guest worker” program that made it okay for Mexican labor to be brought in seasonally to work on cotton farms and other manual jobs (“stoop labor,” it’s called in the films).

Anyway, the film carefully explains that these are really bad jobs, so they’re hard to fill. The issues are familiar: Even in the pre-Lou Dobbs era, people were angry that these supposedly job-threatening outsiders are allowed. Read more

[ –> Details on Sponsored-Film Virtual Festival are here.]

“America is busy now!” this curious film, “The Machine: Master Or Slave?“, begins.

What seems at first like exciting propaganda about the “mighty crescendo of production” revolutionizing the World War II-era United States turns out to be something a little more complicated. What will happen, the film asks, when the “defense emergency” is over, and all the machines used in that effort will instead be used for “making goods people need for living”?

Rumors of layoffs, fear of lost jobs and, perhaps, a return to the pre-War economy – that is, the Depression. The villain: “the new labor-saving machine.” It’s good news for the stockholders, but not so good for the workers. There’s a long montage of machine efficiency, scored with frantic music. That’s the problem: The machines are too efficient! Consumers aren’t buying fast enough! Read more

A Coach For Cinderella

[ –> Details on Sponsored-Film Virtual Festival are here.]

This nine-minute film from 1937 was made on behalf of the Chevrolet Motor Company, by well-known industrial film company the Jam Handy Organization.

A pretty nicely executed piece of Technicolor animation, the film tells – as the title suggests – the familiar story of Cinderella. That’s right, she can’t make it to the ball because she has “no coach.” So her little friends set about making her a dress and coach, etc. – all pretty straightforward (except maybe for the bit where you can hear Cinderella being briefly slapped around offscreen, which is slightly disturbing). Read more

Posted Under:

Olde News,

Sponsored Film Festival

This post was written by Rob Walker on April 23, 2008

Comments Off on Murketing’s Sponsored Film Virtual Festival: “A Coach For Cinderella”

To Market, To Market.

[ –> Details on Sponsored-Film Virtual Festival are here.]

For reasons that aren’t clear to me, part one is in black and white, part two is in color.

“Like the waters of a mighty ocean, people also represent a mighty force,” announces the narrator of “To Market, To Market,” a 1942 film commissioned by General Outdoor Advertising Company, identified in The Field Guide To Sponsored Films as a “major billboard and poster company.” The point of the film: “to convince ad buyers of the value of outdoor advertising.”

After all, the “mighty force” that people represent, the narrator continues, is “known as consumer power.” Read more

[ –> Details on Sponsored-Film Virtual Festival are here.]

It’s pretty obvious that I’d be interested in a film called “Things People Want.” That’s kind of my beat.

In this case, this 20-minute, 1948 film, produced by the Jam Handy Organization for Chevrolet, tells us a story about two kinds of people: those who want things (you), and those “who help them get what they want” (salesmen). The protagonist is a young salesman named Evans, played by none other than John Forsyth (who will always be Blake Carrington to me). Read more

Posted Under:

Olde News,

Sponsored Film Festival

This post was written by Rob Walker on April 21, 2008

Comments Off on Murketing’s Sponsored-Film Virtual Festival: “Things People Want”

Some time ago now, Rick Prelinger sent me a book he’s put together, The Field Guide to Sponsored Films. (For quick refresher on Mr. Prelinger and his work, see this earlier post.) The book is intended for scholars, and available from the National Film Preservation Foundation. (Click here, then on “cooperative projects,” then on “The Field Guide To Sponsored Films” for more information, including how to request a copy or download one.)

Some time ago now, Rick Prelinger sent me a book he’s put together, The Field Guide to Sponsored Films. (For quick refresher on Mr. Prelinger and his work, see this earlier post.) The book is intended for scholars, and available from the National Film Preservation Foundation. (Click here, then on “cooperative projects,” then on “The Field Guide To Sponsored Films” for more information, including how to request a copy or download one.)

Compiled by Rick Prelinger of the Internet Archive with the help of scores of scholars, collectors, and archivists, The Field Guide to Sponsored Films singles out 452 sponsored motion pictures notable for their historical, cultural, or artistic interest. The 152-page annotated filmography includes indexes, repository information, and links to works viewable online.

I spent a bit of time going through this — not reading every word, but browsing, and reading up on films with interesting titles — and when possible, checking out the actual films via the Internet Archive mentioned above.

In the days ahead I’ll post more about several of the films I watched — and I’m giving this limited-run series the title, “Murketing’s Sponsored-Film Virtual Festival.”

I’ll start later this afternoon.

Meanwhile, I just want to mention one of the films I read about and really wanted to see, but that apparently isn’t available online. Made in 1954,by production company Sarra Inc., it was titled, The Secret of Selling the Negro. (They mean selling to “the negro,” of course.) The Field Guide says: Read more

Annie Kopchovsky … was a Latvian immigrant living in a tenement in Boston with her husband and three young children. Spying the unlikeliest of business opportunities for someone in her position, she boasted to the press that she intended to bicycle around the globe in fifteen months, raising money for her journey along the way. …

By the time she left Boston in 1895, Kopchovsky had attracted enough attention that the Londonderry Lithia Spring Water Company paid her $100 to adopt the surname “Londonderry” for the duration of her trip.

Q&A with the author of a new book about Kopchovsky/Londonderry is here.

[Thanks Sara!]

Posted Under:

Murketing,

Olde News

This post was written by Rob Walker on March 5, 2008

Comments Off on Murketing in history: How Annie “Londonderry” got her name

"

"

Kim Fellner's book

Kim Fellner's book  A

A