Q&A: Rosemary Williams, Behind The Wall of Mall

A couple of weeks ago I journeyed out to the Dumbo Arts Center to see an exhibition called Point of Purchase. One of the pieces on view there was a big wall of shopping bags, called The Wall of Mall, by an artist named Rosemary Williams. I was interested to learn that there was also a podcast associated with this piece. I signed up for that, and checked out some of Williams’ earlier projects at her site. A lot of her work is right up my alley — projects like Bodega Booty (a “recreation of a New York City bodega” functioning partly as “a love poem” to such stores), and CEO Views, in which we get to look out the windows of some powerful New Yorkers, and hear them talk about their vantage-points, in every sense of the term.

A couple of weeks ago I journeyed out to the Dumbo Arts Center to see an exhibition called Point of Purchase. One of the pieces on view there was a big wall of shopping bags, called The Wall of Mall, by an artist named Rosemary Williams. I was interested to learn that there was also a podcast associated with this piece. I signed up for that, and checked out some of Williams’ earlier projects at her site. A lot of her work is right up my alley — projects like Bodega Booty (a “recreation of a New York City bodega” functioning partly as “a love poem” to such stores), and CEO Views, in which we get to look out the windows of some powerful New Yorkers, and hear them talk about their vantage-points, in every sense of the term.

I decided to see if Williams would be willing to answer a few questions, and I’m pleased to say she was. A former New Yorker, these days she’s living (and teaching and making art) in Minnesota, not so far from the Mall of America, which turns out to be quite relevant to her podcast, “Rosemary goes To the Mall.”

Let’s start with the obvious questions. “Rosemary Goes To The Mall” is sort of a spinoff of the Wall of Mall, “a giant sculpture made out of shopping bags from the Mall of America.” What were you hoping viewers of the Wall of Mall would take away from it?

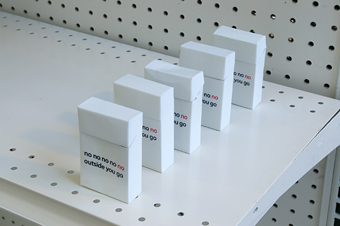

The “Wall of Mall” is meant to be an overwhelming representation of the “brandedness” of our daily lives. I was trying to respond to the Mall of America as iconic architecture, but also as a place which embodies our society’s obsession with stuff, and the ever increasing involvement and identification with manufactured items, the way they imbue status and provide a kind of weird personal satisfaction. I’m not saying that when I was a kid we didn’t want all that stuff and now we do, but there has been a definite creep of national chains overtaking the local store, for better or for worse. On the one hand, this provides a kind of safety, because you know what you are going to get at Starbucks, or the Gap, and it lessens the amount of work one has to do to get a satisfactory coffee, pair of jeans, etc. On the other hand, there is a sameness that is creeping in, which is rarely countered.

So in trying to react to the largest mall in the U.S., I originally had this idea of a giant wall covered in logos. I wasn’t sure whether the logos would be hand-drawn, or more slickly represented. Eventually I got around to the idea of bags, possibly making my own. It came to me that the piece would be strongest with the actual shopping bags, because there is a common experience and narrative to the bags that most people can relate to — namely shopping as a necessity or pastime. Of course, then I discovered, as the podcast listeners will know, that they don’t just give bags out, unless you buy something. That started my epic shopping journey and a conversation in my head that ultimately became “Rosemary Goes to the Mall.”

So in trying to react to the largest mall in the U.S., I originally had this idea of a giant wall covered in logos. I wasn’t sure whether the logos would be hand-drawn, or more slickly represented. Eventually I got around to the idea of bags, possibly making my own. It came to me that the piece would be strongest with the actual shopping bags, because there is a common experience and narrative to the bags that most people can relate to — namely shopping as a necessity or pastime. Of course, then I discovered, as the podcast listeners will know, that they don’t just give bags out, unless you buy something. That started my epic shopping journey and a conversation in my head that ultimately became “Rosemary Goes to the Mall.”

In the end, I think that while the “Wall of Mall” is overwhelming physically, its strength really is the story of the bags, and ways that people can explore the individual brands, recognizing places they’ve shopped at, laughing at the funny ones, or examining how overwhelmingly consumer culture composes our environment.

At what point did you know there was a separate project to be done here, apart from the sculpture?

On my first visit to the Mall, after having my requests for bags turned down in a couple major chain stores, in desperation I lied in Eddie Bauer about needing a bag because my bag had broken. The whole charade was emotionally trying and exhausting, and I didn’t think I could handle the stress of the rejection, or the lying, so I started buying things as a strategy to get the bags in the most painless manner possible, with no intention of this endeavor being any more than a back story for the Wall of Mall. But I was having real psychological reactions in each store, and I decided at the end of that shopping trip that I wanted to record some of these reactions in an audio journal. I had a feeling for the kind of tone I wanted to attain — the present tense, an in-the-moment play-by-play of the shopping trip. I recorded it, and really thought I had captured something interesting, and knew that now I was going to do this for the whole Mall.

At first I thought it was going to be an insanely long video project with images of the products. But in bouncing ideas around, I came to the conclusion that it should be a podcast, and that each shopping trip would be a separate episode. The next time I went shopping, which was nearly a month later, I had pretty well worked out what I was trying to do, and was able to stay consistent with the persona, the tone, and the sense that there was a narrative arc to each shopping trip.

When did you make the recordings? You weren’t doing these recordings while you were at the mall were you? Sometimes it almost seems that way, but the sound quality makes me think that’s not likely.

I made the recordings back at the studio at the end of each day of shopping. I wanted them to feel like you were at the Mall, inside my head. I took notes while I was shopping so that I could remember details for when I recorded the audio. In the recording process I wanted to retain decent sound quality, and also needed a little space from the immediacy of the experience to make the narrative of the audio work.

What’s gotten me hooked on the podcast is that relatively early in your adventure, you started a) thinking about buying stuff that you didn’t want to return, and then b) flat-out buying stuff that you didn’t want to return. Early on you look at some pajamas at Nordstrom and you seem really torn: you like them, but you don’t need them, they’re too expensive, but they’re kind of great — but they’re just pajamas for crying out loud, etc. You imply in the podcast that you and your husband don’t have a whole lot of extra money to throw around. Was this a new moment for you, not just in the life of this project, but in your life as a consumer, really confronting all this so thoroughly?

As a consumer, I have for most of my life been locked out — either by choice or circumstance — from any true appreciation of shopping. Shopping is in many ways a hopeful endeavor, because one hopes to attain a kind of completeness from it (I would look so cute in these jeans and then everyone will know how cool I am), but for many people, myself included, it is a very stressful experience. Anxiety and guilt about money, and weighing the somewhat selfish desire for this external polish against the stress of having to pay for it — what it might mean later in the month, when your partner sees the credit card bill, or when you need to, for example, buy groceries.

As a consumer, I have for most of my life been locked out — either by choice or circumstance — from any true appreciation of shopping. Shopping is in many ways a hopeful endeavor, because one hopes to attain a kind of completeness from it (I would look so cute in these jeans and then everyone will know how cool I am), but for many people, myself included, it is a very stressful experience. Anxiety and guilt about money, and weighing the somewhat selfish desire for this external polish against the stress of having to pay for it — what it might mean later in the month, when your partner sees the credit card bill, or when you need to, for example, buy groceries.

If you can imagine a writer and an artist living together in Brooklyn, and their tremendous earning power, then imagine them starting to have kids, you can maybe imagine the context for our broke-ness. Moving to Minnesota and my having a real job for the first time since I had my first child has improved things mightily, but we’re still not exactly rolling in it. On top of that, I spend ridiculous amounts of money to produce work that is pretty hard to hang on the wall over your couch.

So, I would say that I had very little experience shopping in any concerted way. The shopping I did at the Mall of America was really new to me, because I started to allow myself to look at things and really think about what they might mean to me if I owned them. The seduction of the pajamas, for instance, was intense for me. Who needs a pair of $70 pajamas? But there they are, and they are really cute. No one will see you in them, except your husband, who will wonder why you’re not wearing your ratty t-shirt tonight. But somehow they made me think I would feel special in them. It was a really funny thing for me to toy with the idea of being a person who could have these things. At the same time, they still have to be paid for. Since this project ended I have thankfully gone back to being my old not-shopping self again.

Why didn’t you just buy stuff you knew you didn’t want, just pick the most awful thing in the store every time?

Yes, well. That would have been smart, no? I think I intended to just walk into stores, pull something, anything, off the rack, and purchase it. But almost immediately I started making choices, and got into this real psychological relationship with those choices. It felt like I needed a narrative to fit myself into, in order to do what I had to do.

By the third episode, you’re openly worried about spending too much money. I assume that you really wanted the stuff you kept, but how much of it is stuff you figure you would have bought anyway, vs. stuff you bought because you were exposed to it?

As a person who only goes shopping when I absolutely have to (all my underwear has holes, or I can’t find any matching socks) I would have to say that much of what I bought and kept I would not normally have bought. Which is not to say that it is that extraordinary. It’s just that I don’t tend to buy even things I really need. I rationalize and wait and try not to notice that my glasses fall off my ears because they’re seven years old. I just don’t like making purchases having to do with personal stuff like that. Now I am kind of a computer geek and have spent plenty of money on video and audio equipment, nice flat-screen Apple monitors, Mboxes, and things like that. But a new pair of jeans… It’s a rare occasion. I actually get a lot of my new pairs of jeans from my friend Nicole, who is the same size as me, is a much more enthusiastic shopper than I am, and who clearly sees me as a good target for the stuff she doesn’t want. I suspect I’m a bit of a charity case.

Most of what I did not return to the Mall fell into one of two categories: junk from stores that did not accept returns; or new rather ordinary things like t-shirts and jeans. However, there were a few things I splurged on, like this really cool pair of Gravis sneakers from a skate shop. I remember specifically fretting to Nicole (my jeans source) about wanting to keep that pair of sneakers and her telling me I deserved them. I didn’t really believe it, but I took her advice. Maybe this is why friends shop together.

Do you think it’s harder to return something, as opposed to simply not buying it in the first place? Slightly harder — or exponentially harder?

I think it’s a lot harder if you really like it. It wasn’t hard to return the $100 Stella McCartney yoga mat, because although I do yoga and could use a new mat, I think that this particular item is obscenely expensive and frivolous. However, there were a few things that were very hard for me to return because a part of me really longed for them. If I had never really had them in my possession, I would have had that internal struggle in the store, and then forgotten about them. As it was, while I avoided the internal struggle in the store, I prolonged the agony afterwards.

I’m kind of enjoying the suspense right now, so I don’t want you to give away too much about how it all turns out, but if you want to say: Are there things you now wish you hadn’t bought? And are there things that you wish you had bought (or kept)?

I kind of wish that I had kept the gold lame Puma gym bag. I never, ever would have used it, but my husband even tried to get me to keep it as a momento. However, I was starting to realize the obscene amount of money I had spent doing this project, and brought the bag back to put a band-aid over the bleeding hole in my credit card.

There are a few things I wish I hadn’t bought — a shirt or two that I purchased after getting caught up in the moment, wore a couple times, and then couldn’t return. I also regret my Nike Free Zen walking shoes, because they ripped in the heels after not too long, and while they still work, they seem like a bum deal.

Most of it I don’t regret at all, though I am still dealing with the financial ramifications of my splurges.

Speaking of which: Did your credit card company get in touch with you, about the weird spike in spending — and the even weirder spike in return credits?

Interestingly, my credit card company didn’t ever notify me, even though there was tremendously unusual activity on my account. This leads me to suspect that’s because the level of activity didn’t seem that unusual to them, based on the purchases most people make.

At the beginning of the podcast series I wasn’t sure I was going to enjoy it, because early on you talk about feeling physical revulsion toward the Mall of America. I’ve been to the Mall of America myself, I understand that feeling, but on the other hand it didn’t seem particularly surprising. It was the way the shopping and your thinking about the various objects you were exposed to that hooked me.

I am definitely involved in work that is engaged with the common culture, and taking a critical stance in relation to it. However, the most boring thing in the world to me is political artwork made by predictably “alternative” thinkers who pooh-pooh “normal” peoples’ outlooks on life, or who take really obvious positions in relation to corporate America, or politics. What is interesting to me is exploring the humanity of ambiguous realities of our culture. For example, in my video project “CEO Views,” I convinced CEO’s and other senior executives of New York City companies to let me videotape their office views and do an audio interview about what they liked about these views. At the time I made that piece, I got some criticism that I was being too sympathetic to the CEO’s, that what I really needed to do was crash into their offices in a Michael Moore-type scenario, and challenge them on their corporations’ practices.

I am definitely involved in work that is engaged with the common culture, and taking a critical stance in relation to it. However, the most boring thing in the world to me is political artwork made by predictably “alternative” thinkers who pooh-pooh “normal” peoples’ outlooks on life, or who take really obvious positions in relation to corporate America, or politics. What is interesting to me is exploring the humanity of ambiguous realities of our culture. For example, in my video project “CEO Views,” I convinced CEO’s and other senior executives of New York City companies to let me videotape their office views and do an audio interview about what they liked about these views. At the time I made that piece, I got some criticism that I was being too sympathetic to the CEO’s, that what I really needed to do was crash into their offices in a Michael Moore-type scenario, and challenge them on their corporations’ practices.

But where my interest lay was in what the view of power really looks like. What shocks people about that piece is the humanity of the (mostly) guys who are interviewed, and how they see themselves in relation to society. To me, it is a much more subtle critique of power, which is not solely a force that works against the majority of people — in fact, what would New York City look like architecturally without big business “powering” its economy? And would it have its vibrant artistic culture without major corporations adding to the societal mix? I could go on and on, but these are the paradoxes I am interested in exploring, and getting people to think about in my work.

I think that the story of my own seduction at the Mall of America brings a level of humanity to the podcast and the sculpture. It is not just a one-note criticism of corporate America. There is a really human and psychological component here that is important to understand and engage with. At the same time, if we are going to become less dependent on products and lifestyles that are tough on the environment, for example, or if we are to find our way to a less materialistic culture, it is going to require all of us facing our shopping demons.

Do you think this podcast has any effect, one way or the other, on the meaning (or message or however you would like me to characterize it) of the Wall of Mall itself?

Absolutely. While you can experience one without the other, I think the podcast allows the viewer to delve much more deeply into the story that the bags tell. The feedback I got from the current exhibition of both pieces in “Point of Purchase” at the dumbo arts center in Brooklyn is that going back to the Wall after listening to an episode or two of the podcast gave people the chance to relive my shopping experience (and some of their own) by finding the bags from specific stores on the Wall. I think that conversely, the Wall gives a physical presence to an ephemeral project. The stuff is gone, or being worn, or shoved into a corner of my desk drawer, but the bags remain as evidence of the whole escapade.

I can’t thank Rosemary Williams enough for the time she took to offer such thoughtful answers to my questions. If you can make it to Point of Purchase, you should; and whether you can do that or not, I recommend the Rosemary Goes to the Mall podcast.

"

"

Kim Fellner's book

Kim Fellner's book  A

A