The No Mas Q&A: [Pt. 1] Cassius Clay, Appropriation, Sport, Free Speech, and the Law

One of the projects on the brand underground scene that I’ve been sort of fascinated by is No Mas. The man behind it is Mr. Chris Isenberg. You’re going to get the full scoop below, but here are the basics on him. When I approached him for a Q&A, I had high hopes that I’d get something interesting out of it, but turns out he blew my expectations away. In fact, there was so much interesting material that I’ve decided to make the unprecedented move of turning it into a two-parter. Today’s installment covers some of the most thoughtful material on logo/visual remixing, intellectual property, and free speech — not to mention sports and culture — that I’ve encountered anywhere.

Part two will be in Monday, but meanwhile if the issues above are relevant to you, I encourage you to take the time to read the below.

Q: So I’m curious about the initial decision to start No Mas. Did you see it as a brand, as an art project, as a business, all of the above?

A: I definitely did not have a clear idea of starting a “brand” in the way I now think of No Mas as a “brand”, when I made the first t-shirt with a No Mas label in 2004.

Sometime in about 2001 I think, I saw a picture from 1964 of Muhammad Ali, at that time called Cassius Clay, training at the 5th Street Gym in Miami. The photo was just before the 1964 “shock the world” fight with Liston. In the photo, he’s wearing a t-shirt that says Cassius Clay in a sideways script font that looks very much like it was inspired by the coca-cola script.

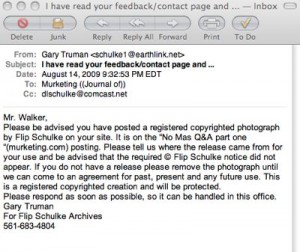

The picture that was here is not here anymore.

It’s funny, Ali was really doing the exact same thing that a lot of us do now. He kind of appropriated and parodied the visual identity of the coca-cola brand to lend power to his own personal brand. That’s classic Ali. Not only was he the greatest fighter, but he was the greatest promoter and marketer. Anyway, I just wanted that Cassius Clay t-shirt really badly. So I made a run of about twelve at a screenprinter in Brooklyn. I wore them myself and I gave them to a few friends.

Wearing this particular shirt in New York City was like conducting a very complicated sociological experiment. Here I am, this white, Jewish kid wearing a shirt emblazoned with a name Muhammad Ali rejected as a slave name. It is a name that has the power of celebrity but also the power of taboo. Muhammad Ali was furious at fighters in the sixties and seventies who still called him Cassius Clay. He famously tortured Ernie Terrell who refused to call him Ali, yelling, “What’s my name fool?” as he pummeled him in their 1967 bout.

So for the people that noticed the shirt it usually produced one of two reactions:

One was basically, “Yo, that’s dope.” “That’s the coolest t-shirt I’ve ever seen.” Etc. I am not gassing myself here because all it really was a well-timed reproduction of Ali’s own work, but literally I would get at least four or five comments every time I wore that shirt out. And a lot of times the conversation ended with, “Where can I get it?” So it became clear really quickly there was a market for this product.

But maybe one in ten or twenty times someone, usually a black man above the age of forty, would want a clarification from me about how I was wearing that shirt. What I was trying to say by wearing it. This conversation was usually a little confrontational at first and might start with: “You know that’s not his name anymore?” “That must be a really old shirt.” “If the man was here he’d knock you out.” But when I got into the history of the graphic and it became clear that I knew a lot about Muhammad Ali and that I was celebrating what this great man did in 1964, these conversations usually turned extremely friendly and developed into interesting discussions of boxing and cultural history or the person’s personal remembrances of Ali and his various fights. I started carrying a Xerox picture of the photo the graphic came from so I could show people who wanted to know about it (and also to avoid potential beatdowns).

But maybe one in ten or twenty times someone, usually a black man above the age of forty, would want a clarification from me about how I was wearing that shirt. What I was trying to say by wearing it. This conversation was usually a little confrontational at first and might start with: “You know that’s not his name anymore?” “That must be a really old shirt.” “If the man was here he’d knock you out.” But when I got into the history of the graphic and it became clear that I knew a lot about Muhammad Ali and that I was celebrating what this great man did in 1964, these conversations usually turned extremely friendly and developed into interesting discussions of boxing and cultural history or the person’s personal remembrances of Ali and his various fights. I started carrying a Xerox picture of the photo the graphic came from so I could show people who wanted to know about it (and also to avoid potential beatdowns).

One guy said to me once at the end of the talk, “That name was good enough for his momma, it should have been good enough for him.” That’s not at all what I was trying to say by wearing the shirt, but I think to the extent that someone perceived that to be my point, it was definitely potentially an incendiary garment, which also, of course, made it exciting to wear.

So particularly from these interactions, the discussions that came out of people challenging my right to wear this shirt or wanting to get into the politics of the name change, I also realized right away that in addition to there being a market for the sort of shirts I would make, the t-shirt could unequivocally be a medium. Not just a conversation-starter in the way that wearing a construction helmet with two built in beer funnels might be a conversation-starter, but a starter of a particular kind of conversation about sports and history and race and religion that was just as deep and provocative as one an art show or a movie or a book might inpsire, but that was even more immediate because it could start in two seconds with a total stranger on the subway or in an elevator.

I knew Isa from Nom de Guerre from hanging out in Williamsburg and I showed him the shirts and asked if he would sell them, and he was down, and they sold really well there. And then I realized all of a sudden that I had a lot of ideas for sports-related shirts. So I made the Pablo Escobar shirt and the Strawberry “say no to drugs” shirt and the “I Ain’t Got No Quarrel with them Vietcong” shirt (more on that below), and they all sold well.

Last year Adidas started making products using the Cassius Clay logo, so I decided to stop for a variety of reasons, but that was the piece that really started my creative process and showed me that a shirt could be a commercial product and a medium at the same time, a mix of art and commerce. (As if anything in the so called ”art world” isn’t.)

I’ll come back to the business side of things in part two of the interview on Monday, but: To what extent to do you think a T-shirt can constitute “speech,” per se? There are some legal issues in there somewhere, but also I think in your case you really do have some ideas, and some other brand underground creators do, too. Although in some other cases it seems more like just an aesthetic. Thoughts?

I am not a lawyer — I basically have just read some articles on the internet and gotten a bit of advice from lawyers — so I am very far from an expert. But this question is interesting and very important to me, so I think about it a lot. I think the status of a garment as a medium for expression is a central question involved in a lot of the work I am making and selling, and to some of the work my peers are making and selling. I also think it’s in many ways very much a live question—not something the courts have really arrived at a definitive answer for.

Start with a very basic personal example. In New York City, you are allowed to sell “artwork” or work that makes political commentary without having a specialized street vendor’s license. I learned about this during the Republican convention and anti-war protests in the city in the summer of 2004. There were huge crowds gathering in Union Square and lots of vendors selling (mainly anti-Bush) political t-shirts and buttons. My office is right near Union Square and I saw an opportunity to sell some of my more political gear in this environment.

I mentioned the “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong” shirts above. I felt that Ali’s statement about the Vietnam war was very relevant to the war in Iraq and I still think so. I felt that wearing the No Mas Vietcong shirt in 2004 (and still in 2006) also implied “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Iraqis,” and I knew that many of the people who bought that shirt wore it in that spirit of protest about us being up in another place we don’t belong. So I went down to Union Square with some of my shirts and started to just sell them off a table, which was fun and actually pretty lucrative, because there were a lot of people looking to buy political shirts in that week for the marches or just to express their displeasure with the Republicans.

At some point some of the Parks Department people started asking the people who were selling for vendors’ licenses and trying to throw some of the sellers who didn’t have them out of the park. And there were a few veteran vendors who were saying that this was unconstitutional and the Parks Department had to respect the First Amendment rights of those sellers, and some of them had some kind of paper from the New York Taxation and Finance Department testifying that their merchandise was political and that they therefore did not need a vendor’s license to sell it on the street. There was kind of a standoff between two Parks people and this group of vendors, and finally a higher-up was brought in and he said yes it was true, you did not need a permit to sell political merchandise. And then the parks people and some cops kind of went to every booth to approve the merchandise as political and they got to mine and said, “Still protesting the Vietnam War?… Alright.” And I was allowed to continue selling there. So I guess for the Supreme Court of Union Square Park the Vietcong shirt was deemed to be political speech protected by the First Amendment, and the fact that it was also commerce was really secondary.

Okay, then what about Muhammad Ali’s “right of publicity”? This was obviously very small-scale selling and did not get the attention of the Ali lawyers, but let’s say that for whatever reason it had. The shirt had Muhammad Ali’s name printed in small letters under his famous pronouncement. Even without the direct identification, I think by the dictates of right of publicity someone might argue on Ali’s side that the shirt derives value from its association to Ali and therefore he deserves to profit from it. As I understand it, that’s what the “right of publicity” is: The right to profit from the use of your own name or license. And clearly people like Robert Sillerman, who now has purchased the right of publicity for Muhammad Ali and Elvis Presley (and paid a millions and millions of dollars for it) are going to vigorously try to protect that right.

Okay, then what about Muhammad Ali’s “right of publicity”? This was obviously very small-scale selling and did not get the attention of the Ali lawyers, but let’s say that for whatever reason it had. The shirt had Muhammad Ali’s name printed in small letters under his famous pronouncement. Even without the direct identification, I think by the dictates of right of publicity someone might argue on Ali’s side that the shirt derives value from its association to Ali and therefore he deserves to profit from it. As I understand it, that’s what the “right of publicity” is: The right to profit from the use of your own name or license. And clearly people like Robert Sillerman, who now has purchased the right of publicity for Muhammad Ali and Elvis Presley (and paid a millions and millions of dollars for it) are going to vigorously try to protect that right.

So then the question is: Does freedom of expression ever trump the right of publicity? And for me that’s a very, very significant question. Because if it doesn’t, then in the case of Ali for example, Sillerman, who owns 80% of Ali’s name and image, would be the sole arbiter of what may and may not be produced and sold which bears the name or likeness of Muhammad Ali. And functionally that means that only big corporations with big dollars, like EA Sports or Adidas, are going to be able to legitimately create objects for sale that reference Ali. And to me that really seems like an injustice, because Muhammad Ali, in addition to being a tremendous athlete, is a political and cultural figure of huge significance. To deny people the right to interact with that heritage and make work with it and profit from that work does not seem fair. But at the same time it also doesn’t seem fair that a man of Muhammad Ali’s standing and accomplishments would have to stand by and get nothing while everyone else profited from the use of his name and likeness and achievements. So right there you’ve got yourself what seems like a real and genuine issue.

And I think the courts are mixed on what to do about this issue. From what I understand there are two main precedents. There is a landmark case from California in 2001, Comedy III v. Saderup. Saderup was an artist that did a charcoal portrait of the Three Stooges on a canvas and then made lithographs and screen-printed t-shirts with his creation. Comedy III controlled the right of publicity to the Three Stooges and they sued Saderup and Saderup ultimately lost the case. The decision centered on the fact that Saderup’s art was not deemed to be “transformative” enough because the likeness was so accurate. And a lot of people were unhappy with this decision and felt very uncomfortable about the idea that the legislative branch of government is going to determine what is “transformative” enough or isn’t, what is “art” and isn’t, and therefore what deserves First Amendment protection and what doesn’t.

And I think the courts are mixed on what to do about this issue. From what I understand there are two main precedents. There is a landmark case from California in 2001, Comedy III v. Saderup. Saderup was an artist that did a charcoal portrait of the Three Stooges on a canvas and then made lithographs and screen-printed t-shirts with his creation. Comedy III controlled the right of publicity to the Three Stooges and they sued Saderup and Saderup ultimately lost the case. The decision centered on the fact that Saderup’s art was not deemed to be “transformative” enough because the likeness was so accurate. And a lot of people were unhappy with this decision and felt very uncomfortable about the idea that the legislative branch of government is going to determine what is “transformative” enough or isn’t, what is “art” and isn’t, and therefore what deserves First Amendment protection and what doesn’t.

The other big case, ETW Corporation vs. Jireh Publishing, was between Tiger Woods and sports artist Rick Rush. Rush did a painting called “Masters of Augusta” that depicted Woods at the 1997 Masters against a background of past Augusta champions, and in 1998 the publishing house run by Rush’s brother released an edition of 250 seriagraphs that went for $700, and then a smaller-sized lithograph in an edition of 5,000, for $15 each.

The other big case, ETW Corporation vs. Jireh Publishing, was between Tiger Woods and sports artist Rick Rush. Rush did a painting called “Masters of Augusta” that depicted Woods at the 1997 Masters against a background of past Augusta champions, and in 1998 the publishing house run by Rush’s brother released an edition of 250 seriagraphs that went for $700, and then a smaller-sized lithograph in an edition of 5,000, for $15 each.

Woods sued Jireh Publishing, claiming that the selling of these prints violated his right of publicity — and he lost in Federal District Court. The judge made a ruling which said that Rush’s work was “an artistic creation seeking to express a message.” And she also insisted, “The fact that it is sold is irrelevant to the determination of whether it receives First Amendment protection.” I think this was upheld in District Court after appeal, and I am not sure what’s going on now, if it’s going to the Supreme Court or not. But there are really powerful groups and individuals on both sides—mainly celebrities, actors and athletes versus news organizations.

To me this decision protects my rights with No Mas to make artwork about athletes—especially when that artwork also deals in some way with the historical, political and cultural legacy of that athlete. For our gallery show in Chelsea last October (Fall Classic: Remembrances and ruminations on the Preciptous Declines of our Sporting Heroes), I commissioned the artist Mickey Duzyj to make works about Mike Tyson. There were original pen-and-ink drawings, there were editoned prints (250) and now this year we are releasing a wider-release print and skateboards with the artwork.

And I think at this point trying to argue that a t-shirt could not also be an acceptable medium for the sale of artwork would be philosophically difficult. Why is a garment any less a candidate to be a work of art than a piece of paper? It seems that once you have moved from saying only the original piece is protected to saying reproductions of that piece are protected, it’s hard to say what objects at that point can and can’t be protected. A poster, a magnet, a greeting card, a t-shirt, a skateboard a coffee cup, whatever.

So I am very much hoping that the courts continue to go in this direction of concluding that the First Amendment is a higher right and a more valuable right than the right of publicity, and I think for us in the t-shirt business it’s a really good decision.

This fall I began to release a series of artist series t-shirts with artist portraits of athletes. They are limited editions, and each come with a hangtag hand-signed by the artist; to me this makes them the legal equivalent of Rush’s lithographs (there are actually a lot fewer of these t-shirts than his Tiger prints) and I believe that my right to make these products is protected.

Other work I’m doing brings up other issues and questions: trademarks and logos and rights of parody and satire, the legal difference between embellishing vintage garments and making new garments, but maybe that’s a subject for another day….

On Monday: Part 2: Art, Writing, Business, and the “Baghdad Oilers.”

"

"

Kim Fellner's book

Kim Fellner's book  A

A

Reader Comments

I liked this paella of ideas–the law discussion was also very clear. I have been in Louisville a lot in the past year. Muhammed Ali Blvd. it isl

good work

Ricardo (Schweitzer)

I know young Isenberg; he’s bright, independent, and, for a youngster, well-travelled. He

listens well, and he also listens to himself, as he shoud. Independent, daring and inventive, he has a bright future ahead of him.

Great interview. Eager for more of this deep dive into culture, race, art, etc.