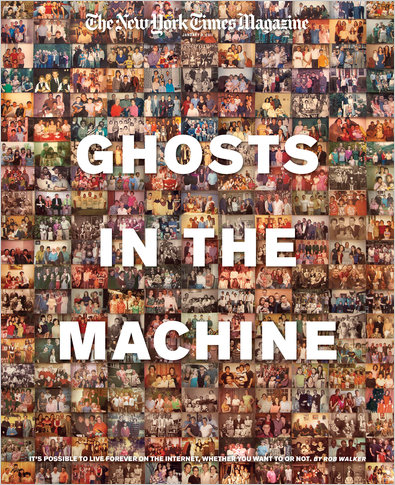

In The New York Times Magazine: Ghosts In The Machine

I’ve mentioned this everywhere else, so may as well note it here: I have a cover story for the Times Magazine this coming Sunday about “digital legacy.”

Suppose that just after you finish reading this article, you keel Lisinopril over, dead. Perhaps you’re ready for such an eventuality, in that you have prepared a will or made some sort of arrangement for the fate of the worldly goods you leave behind: financial assets, personal effects, belongings likely to have sentimental value to others and artifacts of your life like photographs, journals, letters. Even if you haven’t made such arrangements, all of this will get sorted one way or another, maybe in line with what you would have wanted, and maybe not.

But many of us, in these worst of circumstances, would also leave behind things that exist outside of those familiar categories. Suppose you blogged or tweeted about this article, or dashed off a Facebook status update, or uploaded a few snapshots from your iPhone to Flickr, and then logged off this mortal coil. It’s now taken for granted that the things we do online are reflections of who we are or announcements of who we wish to be. So what happens to this version of you that you’ve built with bits? Who will have (https://openoralhealth.org/prednisone/) access to which parts of it, and for how long?

The story is online now. It’s pretty long.

"

"

Kim Fellner's book

Kim Fellner's book  A

A

Reader Comments

Thanks so much for your article this morning. I am teaching a class this term where I’ll most likely use this in place of another reading I had; it will be good for my students to read. I’ve often thought that the idea of immortality is really a comment on memory–that is, people are immortal if they are remembered. Digital technology has put more “memory stuff” out there in the world, sure, and possibly for more of us, but I think one point I’d take issue with in your piece is that media have always played this role; the difference now is primarily one of volume and accessibility. That said, it still doesn’t mean that some stranger to me who dies is immortal to me or everyone, at least not in a clear sense. What it really means is people with whom we have tenuous contact–but who, mind you, already know us–can research us posthumously if they want to, in a way they might not have been able to in the past.

A change, for sure, but a sea change? I’m not sure. More of us are quasi-public, but many of us are really not all that more public than we were. If I were to die after writing this post, my yoga instructor and 6th grade crush might find out more readily than they would have 15 years ago. Might they pore though my online effects? Maybe. Would the world? Probably not.

The other thing is, historians have always been grappling with the issue of abundance and scarcity in the historical record. Think of the mountains of paper we all create daily, yet how difficult it can be to find a cohesive narrative through them. Storage methods seem to always keep the wrong things, leaving gaping holes where we want answers. Our uncertainty about what will be remembered and what saved persists now because we know so little about the solvency of the digital archive. It feels ephemeral, as you say… but it also feels permanent and backed up, and really we have to reason to have any faith that it is either.

Great piece. djp

For the last five years I have been building family history DVDs. I digitized people’s pictures and then recorded them viewing their pictures and telling their family stories. I then included their narration, edited, and produced DVDs of “Their Family’s Story”.One question I always got was, “How long are these DVDs going to last, what’s the next format going to be?”

To answer those question I came up with this.

The Hereafter, an unique iPhone and web application for everyone. The application makes it easy to create and visit memorials of family and friends who have passed away. These memorials are the perfect place to store those treasured family stories. The memorials are created by taking a picture of a gravestone and using the GPS function of the iPhone. This builds a permanent address based on the name on the gravestone and it’s location, something that will not change. Once a memorial is created you can leave condolences, pictures, memories, videos of anything you can digitize even the stories I have produced. All contributed content is considered in the public domain open to all to view and read. This provides future generations a familiar, comforting experience of visiting the memorial’s location in the cemetery. A convent and safe place to put that old box of Grandma’s pictures you have scanned. The application is also a “memento mori”, a reminder of our own mortality.

I’ve realized that the memorials are for more than preservation. They allow the user “contributor“ to influence how future generations view your relationship with this loved one. These stories that a placed on the site reflect not only on the deceit but on the person leaving the story.