“Their four sons often sleep huddled together to pool body heat.”

That’s from a Times Style section story, referring to a couple going to extremes to reduce their carbon footprint; it’s a trend story kind of thing, about hardcore eco-types.

Some people may view [them] as role models, pioneers who will lead us to a cleaner earth. Others may see them as colorful eccentrics, people with admirable intentions who have arrived at a way of life close to zealotry. To others they come across as “energy anorexics,” obsessing over personal carbon emissions to an unhealthy degree, the way crash dieters watch the bathroom scale.

To me this story made such people seem more or less like a freak show. I wonder about stories like this, if their net impact isn’t to make the whole notion of changing your lifestyle in “green” ways seem like a marginal, vaguely comical pursuit — something other people do.

Mr. Nocera’s column today contains this passing assertion:

I contend that this financial crisis is going to cause an entire generation to become debt-averse, as our parents were after the Depression.

Possibly so. Here’s a bunch more debt/credit thinking:

Here, Virginia Postrel makes the case that “the expansion of consumer credit is one of the great economic achievements of the past century.”

Here, Michael Mandel of BusinessWeek and Johs Worsoe of Union Bank tell Marketplace that in recent years growth was too credit-driven and behavior change is necessary.

Here, Robert Reich argues the problem hasn’t been people living beyond their means via debt, it’s been stagnant wages forcing them to take on too much debt just to keep up. (Via Marginal Utility.)

Here, Virginia Prescott of public radio show Word of Mouth interviews the maker of a film called I.O.U.S.A, which argues “America must mend its spendthrift ways or face an economic disaster of epic proportions.”

UPDATE: One more note of interest on an NPR page, here: “Since 1970, consumption in the U.S. as a percentage of GDP has been at or above 64 percent. These levels are substantially higher than the rates for Germany and Japan.” That’s not a stat I knew.

Since feelings of lost control and so on have been a recurring theme here on Murketing.com lately, I thought I’d pass this along. I read yesterday an article in the Journal of Consumer Research (from the April 2008 issue) that’s summarized on Science Daily as follows: “Feeling powerless can trigger strong desires to purchase products that convey high status, according to new research.”

In three experiments, the authors asked participants to either describe a situation where they had power over another person, or one in which someone had power over them. Then the researchers showed them items and asked how much they would be willing to pay.

After recalling situations where they were powerless, participants were willing to pay more for items that signal status, like silk ties and fur coats, but not products like minivans and dryers. They also agreed to pay more for a framed picture of their university if it was portrayed as rare and exclusive.

The authors describe the implications:

“It suggests that in contemporary America, people use consumer purchases to compensate for psychological states of insecurity. Spending beyond one’s means in obtaining status-related items is a costly coping strategy for dealing with psychological threats such as feeling powerless.”

Well, what do you make of this? Does it ring true?

If nothing else, it offers a counterpoint, or at least an interesting asterisk to, for instance, the assertion from Business Week that a “New Frugality” is upon us: “In the past, consumers have gone shopping the moment the sun came out. But this time? Market researchers trying to divine the consumer psyche are picking up signs that attitudes are changing.” The magazine cites a survey in which consumers say they intend to continue frugal habits currently being forced upon them, even when the economy recovers.

Then again, if you asked consumers whether they’d pay more for a status-object if they felt “powerless,” obviously they’d say no. That doesn’t mean the research cited above necessarily holds water; my point is that asking consumers questions generally leads to consumers giving what they figure is the “right” answer — it doesn’t mean a lot. There’s often a gap between what we say and how we behave.

But you knew that.

Anyway, more on this in the days ahead, I am sure.

Back in February I had a short post pondering what a bad economy meant for the “green” movement. (Funny, February seems like it was a giddy boom period compared to today, eh?) Two more recent views on that question:

A Marketplace report is largely pessimistic: “Financial Crisis Is Not Eco-Friendly.”

A piece on The Big Money, by Eric Pooley, offers a more optimistic view: “Save the Economy, Save the Planet.”

Recently I read Stephen Baker’s book The Numerati, all about “the mathematical modeling of humanity,” and Bob Garfield’s long ode to data mining in Ad Age, which strikes very similar themes about the power of algorithms.

More recently I listened to a 60 Minutes report about the recent troubles on Wall Street and beyond (via podcast). Here’s a bit taken from the news show’s online textual recap of that segment:

These complex financial instruments were actually designed by mathematicians and physicists, who used algorithms and computer models to reconstitute the unreliable loans in a way that was supposed to eliminate most of the risk.

“Obviously they turned out to be wrong,” Partnoy says. [Frank Partnoy, a former derivatives broker and corporate securities attorney, who now teaches law at the University of San Diego.]

Asked why, he says, “Because you can’t model human behavior with math.”

Hm.

What say you? Can human behavior be mathematically modeled, or not?

Not to come across like president of the Jason Zweig fan club or anything, but he has another very good column today, tying some recent research about feelings of lost control and pattern invention to some of the more conspiracy-minded responses to the current market/economic turmoil.

The research is summarized briefly in this Discovery.com article, and at more length in this recent Science Friday radio broadcast (I linked to both of these in the sidebar the other day; much earlier and unrelated Murketing post on the subject of pattern invention, or pareidolia, here). The upshot is that when people feel that they have no control over their circumstances, they are more likely to believe in false patterns and conspiracy theories and the like.

From Mr. Zweig’s column:

In a related experiment, investors who had been stripped of their sense of control by market volatility were convinced that they had read more negative evidence about a company than they had actually seen — and were less willing to buy the company’s stock.

In other words, when our sense of control is threatened, we feel the natural urge to pretend that whatever information we do have is more complete and reliable than it is. Imagining that we know what’s coming next (even if we think it will be bad) gives us a slight feeling of comfort.

Posted Under:

Consumer Behavior

This post was written by Rob Walker on October 7, 2008

Comments Off on Out-of-control pattern invention

It occurs to me that I have an easy rejoinder to those who continue to insist that the last ten years have shown a notable uptick in consumer savvy. That rejoinder is: “Premium denim.”

But maybe I’m wrong about that. Interested as I was to see this brief photo essay of a Kentucky denim factory that “specializes in distressing high-end jeans,” I was really interested in what the photographer said about his visit:

I used to scoff at paying a premium for jeans that come with holes in them already. Then I saw just how much work goes into distressing jeans, and I realized that these people are artists.

Hm. Well, I’m sure they do work very hard and have lots of skill and so on. But is the idea that seeing a lot of work go into something you thought was kind of pointless thereby redeems that thing? Would you find Crocs (or whatever it is you find absurd in consumer culture) more appealing if you knew they were really hard to make?

If this question interests you, don’t miss the spirited debate in the comments appended to the photo essay.

Via BB.

Well, after last week’s posts here on optimism, and pessimism, and optimism vs. pessimism — it’s looking pretty grim out there! As I type, the Dow has fallen 600 points below the 10,000 mark. Other lousy economic news abounds, and the presidential race is disintegrating into bitterness and tomfoolery.

The NYT’s story on how consumers are faring is not exactly shocking: “Full of Doubts, U.S. Shoppers Cut Spending.” Looks like consumer spending for the third quarter will be down 3 percent, per projections, “the first quarterly decline in nearly two decades.”

“The last few days have devastated the American consumer,” said Walter Loeb, president of Loeb Associates, a consultancy, who said he worried that the constant drumbeat of negative news about the economy was becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. “They all feel poor.”

No surprise, then, that the post here last week that got the most response was the pessimism one, which also happened to ask: “Is Main Street a bunch of spoiled overspending babies?” More specifically, I brought up some comments from a Sunday chat show in which some observers contended that one of the issues America is going to have to work through is that many Americans have been living well beyond their means for years, and in denial about it.

The comments were mixed, to say the least. However, I wanted to follow up in a general way to make a broad point that’s not aimed at any of those comments specifically. Read more

As a counterpoint to the anonymous J, mentioned yesterday, there was an unbelievably gloomy roundtable on This Week Sunday, most interesting to me because in addition to the usual beatdowns to government and Wall Street, the participants went after Main Street consumers.

Here’s a link to the video, but I’ll give you the highlights, or lowlights (with selected bolding to underscore the most interesting stuff). The first 10 minutes or so is boilerplate hemming and hawing about the bailout and craven politicians and all that. Then about halfway through, Washington Post writer Steven Pearlstein said: Read more

What’s the difference between rhetoric and cognitive dissonance?

Both can result in points of view that are so biased that they have no connection to reality. But one involves communicative sleight of hand to mislead the reader/listener, while the other involves a deeper form of dishonesty: Dishonesty with the self.

Murketing.com has no interest whatsoever in influencing your vote. But I think this assessment of last night’s presidential debate offers examples of both rhetoric and congnitive dissonance.

It comes from the Web site of the Weekly Standard, a site I read regularly. It begins with an excellent example of rhetoric: Read more

Following up on this earlier post on “source amnesia,” and the tendency for political (and other) mistruths to “stick”: I guess it’s no surprise the topic is getting attention as the current political season reaches ever-more-absurd levels of frenzy. Braulio sends this item from Very Short List:

Earlier this year, political scientists at Duke and Georgia State described the Bush administration’s claims about Iraqi WMDs to a group of adults, then gave those same people a convincing explanation that Iraq did not, in fact, have a WMD program in the works. How did the people react? Liberals became even more convinced that Iraq had no nuclear or chemical weapons; conservatives became even more certain that it did, with 64 percent of them insisting that Saddam was hiding the evidence.

Basically a classic instance of cognitive dissonance, no? (Subject comes up in Buying In, for whatever that’s worth.)

And today I see Freakonomics links to this Washington Post column on the same subject, mentioning the Duke experiment and others. In one, Yale political science prof John Bullock showed subjects the transcript of a NARAL ad that claimed John Roberts supported “violent fringe groups and a convicted clinic bomber.”

Bullock then showed volunteers a refutation of the ad by abortion-rights supporters. He also told the volunteers that the advocacy group had withdrawn the ad. Although 56 percent of Democrats had originally disapproved of Roberts before hearing the misinformation, 80 percent of Democrats disapproved of the Supreme Court nominee afterward. Upon hearing the refutation, Democratic disapproval of Roberts dropped only to 72 percent.

Republican disapproval of Roberts rose after hearing the misinformation but vanished upon hearing the correct information. The damaging charge, in other words, continued to have an effect even after it was debunked among precisely those people predisposed to buy the bad information in the first place.

The upshot of this and other experiments, The Post’s Shankar Vedantam writes, is that “refutations can strengthen misinformation.” And although I happen to have used an example showing this among Democrats, Vedantam says the tendency is “especially” true “among conservatives.”

AdFreak, citing BoingBoing, muses briefly on false memories and branding. One of the cited studies came up briefly in this article (of mine) about brand revival and memory, and in somewhat more detail in the third chapter — if I’m remembering right — of Buying In.

A friend of Murketing writes:

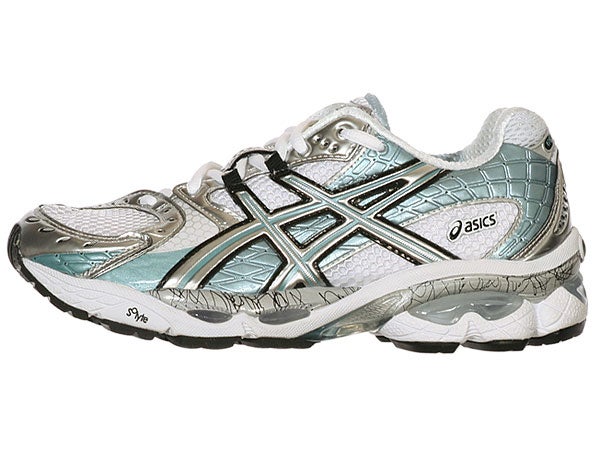

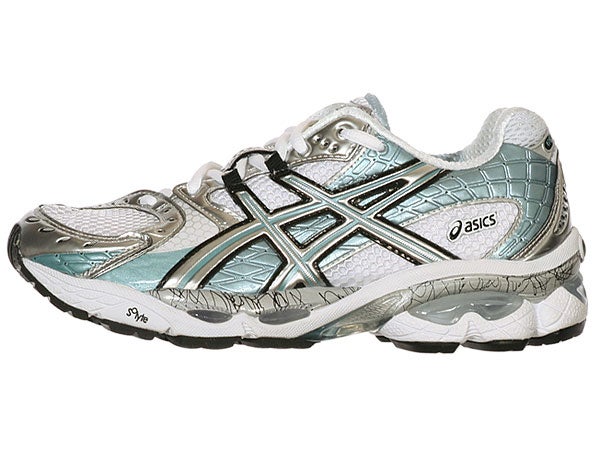

The other day I bought new running shoes, Asics. I like a certain model (Nimbus) which are super comfy, but they are designing progressively uglier, and this latest incarnation is just hideous, with these weird scribbles along the bottom. It also comes in pink and purple (’cause that’s what we gals like).

I like Asics not out of true brand loyalty, but because the shoe does fit me well and is most comfortable. But this tme I nearly bought something else because these are really just plain ugly; I had a chat with the clerk who agreed and said, in fact, every customer is saying the same thing. It’s like Asics has some death wish or something, to drive away customers.

It’s just peculiar how in the running kicks market, some brands never look ugly, and soem seem to go out of their way to look ugly. I guess my question is how loyal are people — can you make a product so aesthetically undesirable that even the faithful will ultimately go away?

Interesting question! Setting aside whether Asics has a design death wish (although if you have opinions on that, let me know), is there a point at which a product is just ugly you’ll switch to a different one even if it means sacrificing something like comfort or performance?

Recently Business Week ran a big package on how companies use the Olympics to show off new innovations they hope will go on to attract more widespread consumer embrace. This morning the WSJ has a story about Michael Phelps that includes this bit suggesting sometimes no particular innovation is required, and mere exposure is enough:

Even the white Speedo parka that Mr. Phelps wore to the starting block before his races prompted consumer demand. Speedo had no intention of selling that item to customers. Now it’s begun ramping up production, says Mr. Brommers, the Speedo marketing vice president.

“People want a piece of history here,” says Mr. Brommers. “We’re trying to get this stuff out the door as fast as we can.”

I was pleased to see somebody pick up on the Andrew Andrew stuff at the end of Buying In, and relate it to magical thinking. That post, on the Psychology Today blog of Matthew Hutson, led me to his article on the subject of magical thinking. Since I’m away from home and I’m going to be a little busy today, I point you to that article if you’re looking for something to read. It may be a bit long to read online, but here’s one bit of interest relating to magical thinking and material culture:

To some, John Lennon’s piano is sacred. Most married people consider their wedding rings sacred. Kids with no notion of sanctity will bust a lung wailing over their lost blanky. Personal investment in inanimate objects might delicately be called sentimentality, but what else is it if not magical thinking? There’s some invisible meaning attached to these things: an essence. A wedding ring or a childhood blanket could be replaced by identical or near-identical ones, but those impostors just wouldn’t be the same.

What makes something sacred is not its material makeup but its unique history. And whatever causes us to value essence over appearance becomes apparent at an early age. Psychologists Bruce Hood at Bristol University and Paul Bloom at Yale convinced kids ages 3 to 6 that they’d constructed a “copying machine.” The kids were fine taking home a copy of a piece of precious metal produced by the machine, but not so with a clone of one of Queen Elizabeth II’s spoons—they wanted the original.

"

"

Kim Fellner's book

Kim Fellner's book  A

A